Department+of+Bio

-

KAIST Reveals Placental Inflammation as the Cause of Allergies such as Pediatric Asthma

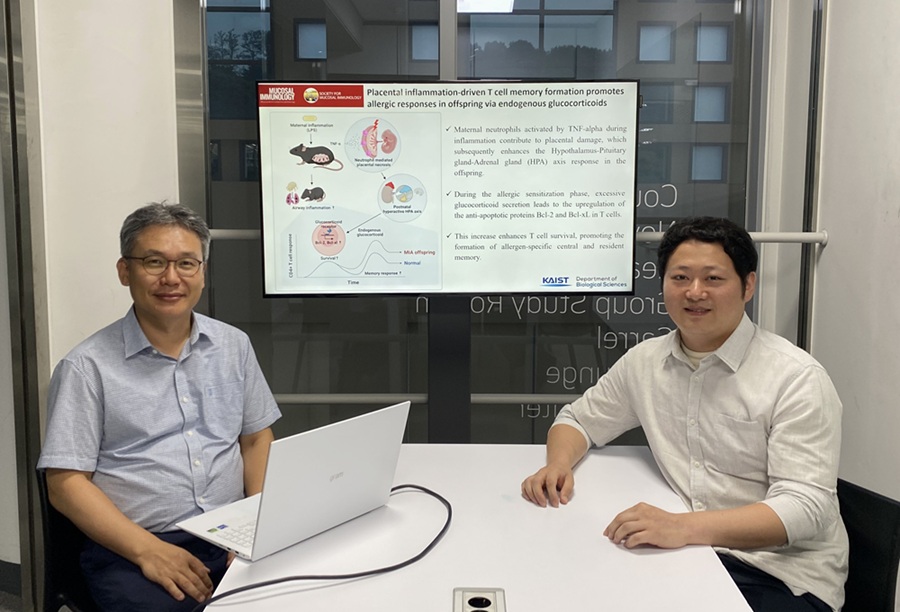

<(From left)Professor Heung-kyu Lee from the Department of Biological Sciences, Dr.Myeong Seung Kwon from the Graduate School of Medical Science>

It is already well-known that when a mother experiences inflammation during pregnancy, her child is more likely to develop allergic diseases. Recently, a KAIST research team became the first in the world to discover that inflammation within the placenta affects the fetus's immune system, leading to the child exhibiting excessive allergic reactions after birth. This study presents a new possibility for the early prediction and prevention of allergic diseases such as pediatric asthma.

KAIST (President Kwang Hyung Lee) announced on the 4th of August that a research team led by Professor Heung-kyu Lee from the Department of Biological Sciences found that inflammation occurring during pregnancy affects the fetus's stress response regulation system through the placenta. As a result, the survival and memory differentiation of T cells (key cells in the adaptive immune system) increase, which can lead to stronger allergic reactions in the child after birth.

The research team proved this through experiments on mice that had excessive inflammation induced during pregnancy. First, they injected the toxin component 'LPS (lipopolysaccharide),' a substance known to be a representative material that induces an inflammatory response in the immune system, into the mice to cause an inflammatory response in their bodies, which also caused inflammation in the placenta.

It was confirmed that the placental tissue, due to the inflammatory response, increased a signaling substance called 'Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α),' and this substance activated immune cells called 'neutrophils*', causing inflammatory damage to the placenta. *Neutrophils: The most abundant type of white blood cells in our bodies (40-75%), playing an important role in innate immunity and killing invading bacteria and fungi.

This damage modulated postnatal offspring stress response, leading to a large secretion of stress hormone (glucocorticoid). As a result, the offspring's T cells, which are responsible for immune memory, survived longer and had stronger memory functions.

In particular, the memory T cells created through this process caused excessive allergic reactions when repeatedly exposed to antigens after birth. Specifically, when house dust mite 'allergens' were exposed to the airways of mice, a strong eosinophilic inflammatory response and excessive immune activation were observed, with an increase in immune cells important for allergy and asthma reactions.

Professor Heung Kyu Lee stated, "This study is the first in the world to identify how a mother's inflammatory response during pregnancy affects the fetus's allergic immune system through the placenta." He added, "This will be an important scientific basis for developing biomarkers for early prediction and establishing prevention strategies for pediatric allergic diseases."

The first author of this study is Dr. Myeong Seung Kwon from the KAIST Graduate School of Medical Science (currently a clinical fellow of gynecological oncology at Konyang University Hospital's Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology), and the research results were published in the authoritative journal in the field of mucosal immunology, 'Mucosal Immunology,' on July 1st. ※ Paper Title: Placental inflammation-driven T cell memory formation promotes allergic responses in offspring via endogenous glucocorticoids ※ DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mucimm.2025.06.006

This research was conducted as part of the Basic Science Research Program and the Bio-Medical Technology Development Program supported by the Ministry of Science and ICT and the National Research Foundation of Korea.

2025.08.03 View 188

KAIST Reveals Placental Inflammation as the Cause of Allergies such as Pediatric Asthma

<(From left)Professor Heung-kyu Lee from the Department of Biological Sciences, Dr.Myeong Seung Kwon from the Graduate School of Medical Science>

It is already well-known that when a mother experiences inflammation during pregnancy, her child is more likely to develop allergic diseases. Recently, a KAIST research team became the first in the world to discover that inflammation within the placenta affects the fetus's immune system, leading to the child exhibiting excessive allergic reactions after birth. This study presents a new possibility for the early prediction and prevention of allergic diseases such as pediatric asthma.

KAIST (President Kwang Hyung Lee) announced on the 4th of August that a research team led by Professor Heung-kyu Lee from the Department of Biological Sciences found that inflammation occurring during pregnancy affects the fetus's stress response regulation system through the placenta. As a result, the survival and memory differentiation of T cells (key cells in the adaptive immune system) increase, which can lead to stronger allergic reactions in the child after birth.

The research team proved this through experiments on mice that had excessive inflammation induced during pregnancy. First, they injected the toxin component 'LPS (lipopolysaccharide),' a substance known to be a representative material that induces an inflammatory response in the immune system, into the mice to cause an inflammatory response in their bodies, which also caused inflammation in the placenta.

It was confirmed that the placental tissue, due to the inflammatory response, increased a signaling substance called 'Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α),' and this substance activated immune cells called 'neutrophils*', causing inflammatory damage to the placenta. *Neutrophils: The most abundant type of white blood cells in our bodies (40-75%), playing an important role in innate immunity and killing invading bacteria and fungi.

This damage modulated postnatal offspring stress response, leading to a large secretion of stress hormone (glucocorticoid). As a result, the offspring's T cells, which are responsible for immune memory, survived longer and had stronger memory functions.

In particular, the memory T cells created through this process caused excessive allergic reactions when repeatedly exposed to antigens after birth. Specifically, when house dust mite 'allergens' were exposed to the airways of mice, a strong eosinophilic inflammatory response and excessive immune activation were observed, with an increase in immune cells important for allergy and asthma reactions.

Professor Heung Kyu Lee stated, "This study is the first in the world to identify how a mother's inflammatory response during pregnancy affects the fetus's allergic immune system through the placenta." He added, "This will be an important scientific basis for developing biomarkers for early prediction and establishing prevention strategies for pediatric allergic diseases."

The first author of this study is Dr. Myeong Seung Kwon from the KAIST Graduate School of Medical Science (currently a clinical fellow of gynecological oncology at Konyang University Hospital's Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology), and the research results were published in the authoritative journal in the field of mucosal immunology, 'Mucosal Immunology,' on July 1st. ※ Paper Title: Placental inflammation-driven T cell memory formation promotes allergic responses in offspring via endogenous glucocorticoids ※ DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mucimm.2025.06.006

This research was conducted as part of the Basic Science Research Program and the Bio-Medical Technology Development Program supported by the Ministry of Science and ICT and the National Research Foundation of Korea.

2025.08.03 View 188 -

Why Do Plants Attack Themselves? The Secret of Genetic Conflict Revealed

<Professor Ji-Joon Song of the KAIST Department of Biological Sciences>

Plants, with their unique immune systems, sometimes launch 'autoimmune responses' by mistakenly identifying their own protein structures as pathogens. In particular, 'hybrid necrosis,' a phenomenon where descendant plants fail to grow healthily and perish after cross-breeding different varieties, has long been a difficult challenge for botanists and agricultural researchers. In response, an international research team has successfully elucidated the mechanism inducing plant autoimmune responses and proposed a novel strategy for cultivar improvement that can predict and avoid these reactions.

Professor Ji-Joon Song's research team at KAIST, in collaboration with teams from the National University of Singapore (NUS) and the University of Oxford, announced on the 21st of July that they have elucidated the structure and function of the 'DM3' protein complex, which triggers plant autoimmune responses, using cryo-electron microscopy (Cryo-EM) technology.

This research is drawing attention because it identifies defects in protein structure as the cause of hybrid necrosis, which occurs due to an abnormal reaction of immune receptors during cross-breeding between plant hybrids.

This protein (DM3) is originally an enzyme involved in the plant's immune response, but problems arise when the structure of the DM3 protein is damaged in a specific protein combination called 'DANGEROUS MIX (DM)'.

Notably, one variant of DM3, the 'DM3Col-0' variant, forms a stable complex with six proteins and is recognized as normal, thus not triggering an immune response. In contrast, another 'DM3Hh-0' variant has improper binding between its six proteins, causing the plant to recognize it as an 'abnormal state' and trigger an immune alarm, leading to autoimmunity.

The research team visualized this structure using atomic-resolution cryo-electron microscopy (Cryo-EM) and revealed that the immune-inducing ability is not due to the enzymatic function of the DM3 protein, but rather to 'differences in protein binding affinity.'

<Figure 1. Mechanism of Plant Autoimmunity Triggered by the Collapse of the DM3 Protein Complex>

This demonstrates that plants can initiate an immune response by recognizing not only 'external pathogens' but also 'internal protein structures' when they undergo abnormal changes, treating them as if they were pathogens.

The study shows how sensitively the plant immune system changes and triggers autoimmune responses when genes are mixed and protein structures change during the cross-breeding of different plant varieties. It significantly advanced the understanding of genetic incompatibility that can occur during natural cross-breeding and cultivar improvement processes.

Dr. Gijeong Kim, the co-first author, stated, "Through international research collaboration, we presented a new perspective on understanding the plant immune system by leveraging the autoimmune phenomenon, completing a high-quality study that encompasses structural biochemistry, genetics, and cell biological experiments."

Professor Ji-Joon Song of the KAIST Department of Biological Sciences, who led the research, said, "The fact that the immune system can detect not only external pathogens but also structural abnormalities in its own proteins will set a new standard for plant biotechnology and crop breeding strategies. Cryo-electron microscopy-based structural analysis will be an important tool for understanding the essence of gene interactions."

This research, with Professor Ji-Joon Song and Professor Eunyoung Chae of the University of Oxford as co-corresponding authors, Dr. Gijeong Kim (currently a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Zurich) and Dr. Wei-Lin Wan of the National University of Singapore as co-first authors, and Ph.D candidate Nayun Kim, as the second author, was published on July 17th in Molecular Cell, a sister journal of the international academic journal Cell.

This research was supported by the KAIST Grand Challenge 30 project.

Article Title: Structural determinants of DANGEROUS MIX 3, an alpha/beta hydrolase that triggers NLR-mediated genetic incompatibility in plants DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2025.06.021

2025.07.21 View 479

Why Do Plants Attack Themselves? The Secret of Genetic Conflict Revealed

<Professor Ji-Joon Song of the KAIST Department of Biological Sciences>

Plants, with their unique immune systems, sometimes launch 'autoimmune responses' by mistakenly identifying their own protein structures as pathogens. In particular, 'hybrid necrosis,' a phenomenon where descendant plants fail to grow healthily and perish after cross-breeding different varieties, has long been a difficult challenge for botanists and agricultural researchers. In response, an international research team has successfully elucidated the mechanism inducing plant autoimmune responses and proposed a novel strategy for cultivar improvement that can predict and avoid these reactions.

Professor Ji-Joon Song's research team at KAIST, in collaboration with teams from the National University of Singapore (NUS) and the University of Oxford, announced on the 21st of July that they have elucidated the structure and function of the 'DM3' protein complex, which triggers plant autoimmune responses, using cryo-electron microscopy (Cryo-EM) technology.

This research is drawing attention because it identifies defects in protein structure as the cause of hybrid necrosis, which occurs due to an abnormal reaction of immune receptors during cross-breeding between plant hybrids.

This protein (DM3) is originally an enzyme involved in the plant's immune response, but problems arise when the structure of the DM3 protein is damaged in a specific protein combination called 'DANGEROUS MIX (DM)'.

Notably, one variant of DM3, the 'DM3Col-0' variant, forms a stable complex with six proteins and is recognized as normal, thus not triggering an immune response. In contrast, another 'DM3Hh-0' variant has improper binding between its six proteins, causing the plant to recognize it as an 'abnormal state' and trigger an immune alarm, leading to autoimmunity.

The research team visualized this structure using atomic-resolution cryo-electron microscopy (Cryo-EM) and revealed that the immune-inducing ability is not due to the enzymatic function of the DM3 protein, but rather to 'differences in protein binding affinity.'

<Figure 1. Mechanism of Plant Autoimmunity Triggered by the Collapse of the DM3 Protein Complex>

This demonstrates that plants can initiate an immune response by recognizing not only 'external pathogens' but also 'internal protein structures' when they undergo abnormal changes, treating them as if they were pathogens.

The study shows how sensitively the plant immune system changes and triggers autoimmune responses when genes are mixed and protein structures change during the cross-breeding of different plant varieties. It significantly advanced the understanding of genetic incompatibility that can occur during natural cross-breeding and cultivar improvement processes.

Dr. Gijeong Kim, the co-first author, stated, "Through international research collaboration, we presented a new perspective on understanding the plant immune system by leveraging the autoimmune phenomenon, completing a high-quality study that encompasses structural biochemistry, genetics, and cell biological experiments."

Professor Ji-Joon Song of the KAIST Department of Biological Sciences, who led the research, said, "The fact that the immune system can detect not only external pathogens but also structural abnormalities in its own proteins will set a new standard for plant biotechnology and crop breeding strategies. Cryo-electron microscopy-based structural analysis will be an important tool for understanding the essence of gene interactions."

This research, with Professor Ji-Joon Song and Professor Eunyoung Chae of the University of Oxford as co-corresponding authors, Dr. Gijeong Kim (currently a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Zurich) and Dr. Wei-Lin Wan of the National University of Singapore as co-first authors, and Ph.D candidate Nayun Kim, as the second author, was published on July 17th in Molecular Cell, a sister journal of the international academic journal Cell.

This research was supported by the KAIST Grand Challenge 30 project.

Article Title: Structural determinants of DANGEROUS MIX 3, an alpha/beta hydrolase that triggers NLR-mediated genetic incompatibility in plants DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2025.06.021

2025.07.21 View 479 -

KAIST Successfully Implements 3D Brain-Mimicking Platform with 6x Higher Precision

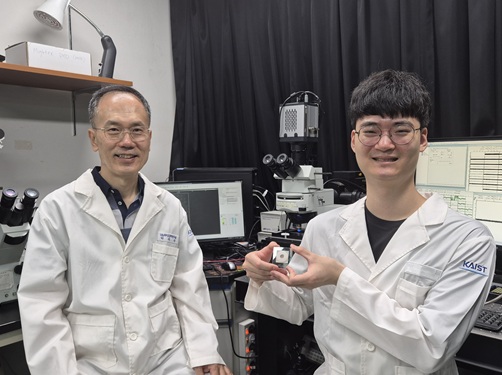

<(From left) Dr. Dongjo Yoon, Professor Je-Kyun Park from the Department of Bio and Brain Engineering, (upper right) Professor Yoonkey Nam, Dr. Soo Jee Kim>

Existing three-dimensional (3D) neuronal culture technology has limitations in brain research due to the difficulty of precisely replicating the brain's complex multilayered structure and the lack of a platform that can simultaneously analyze both structure and function. A KAIST research team has successfully developed an integrated platform that can implement brain-like layered neuronal structures using 3D printing technology and precisely measure neuronal activity within them.

KAIST (President Kwang Hyung Lee) announced on the 16th of July that a joint research team led by Professors Je-Kyun Park and Yoonkey Nam from the Department of Bio and Brain Engineering has developed an integrated platform capable of fabricating high-resolution 3D multilayer neuronal networks using low-viscosity natural hydrogels with mechanical properties similar to brain tissue, and simultaneously analyzing their structural and functional connectivity.

Conventional bioprinting technology uses high-viscosity bioinks for structural stability, but this limits neuronal proliferation and neurite growth. Conversely, neural cell-friendly low-viscosity hydrogels are difficult to precisely pattern, leading to a fundamental trade-off between structural stability and biological function. The research team completed a sophisticated and stable brain-mimicking platform by combining three key technologies that enable the precise creation of brain structure with dilute gels, accurate alignment between layers, and simultaneous observation of neuronal activity.

The three core technologies are: ▲ 'Capillary Pinning Effect' technology, which enables the dilute gel (hydrogel) to adhere firmly to a stainless steel mesh (micromesh) to prevent it from flowing, thereby reproducing brain structures with six times greater precision (resolution of 500 μm or less) than conventional methods; ▲ the '3D Printing Aligner,' a cylindrical design that ensures the printed layers are precisely stacked without misalignment, guaranteeing the accurate assembly of multilayer structures and stable integration with microelectrode chips; and ▲ 'Dual-mode Analysis System' technology, which simultaneously measures electrical signals from below and observes cell activity with light (calcium imaging) from above, allowing for the simultaneous verification of the functional operation of interlayer connections through multiple methods.

< Figure 1. Platform integrating brain-structure-mimicking neural network model construction and functional measurement technology>

The research team successfully implemented a three-layered mini-brain structure using 3D printing with a fibrin hydrogel, which has elastic properties similar to those of the brain, and experimentally verified the process of actual neural cells transmitting and receiving signals within it.

Cortical neurons were placed in the upper and lower layers, while the middle layer was left empty but designed to allow neurons to penetrate and connect through it. Electrical signals were measured from the lower layer using a microsensor (electrode chip), and cell activity was observed from the upper layer using light (calcium imaging). The results showed that when electrical stimulation was applied, neural cells in both upper and lower layers responded simultaneously. When a synapse-blocking agent (synaptic blocker) was introduced, the response decreased, proving that the neural cells were genuinely connected and transmitting signals.

Professor Je-Kyun Park of KAIST explained, "This research is a joint development achievement of an integrated platform that can simultaneously reproduce the complex multilayered structure and function of brain tissue. Compared to existing technologies where signal measurement was impossible for more than 14 days, this platform maintains a stable microelectrode chip interface for over 27 days, allowing the real-time analysis of structure-function relationships. It can be utilized in various brain research fields such as neurological disease modeling, brain function research, neurotoxicity assessment, and neuroprotective drug screening in the future."

The research, in which Dr. Soo Jee Kim and Dr. Dongjo Yoon from KAIST's Department of Bio and Brain Engineering participated as co-first authors, was published online in the international journal 'Biosensors and Bioelectronics' on June 11, 2025.

※Paper: Hybrid biofabrication of multilayered 3D neuronal networks with structural and functional interlayer connectivity

※DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2025.117688

2025.07.16 View 555

KAIST Successfully Implements 3D Brain-Mimicking Platform with 6x Higher Precision

<(From left) Dr. Dongjo Yoon, Professor Je-Kyun Park from the Department of Bio and Brain Engineering, (upper right) Professor Yoonkey Nam, Dr. Soo Jee Kim>

Existing three-dimensional (3D) neuronal culture technology has limitations in brain research due to the difficulty of precisely replicating the brain's complex multilayered structure and the lack of a platform that can simultaneously analyze both structure and function. A KAIST research team has successfully developed an integrated platform that can implement brain-like layered neuronal structures using 3D printing technology and precisely measure neuronal activity within them.

KAIST (President Kwang Hyung Lee) announced on the 16th of July that a joint research team led by Professors Je-Kyun Park and Yoonkey Nam from the Department of Bio and Brain Engineering has developed an integrated platform capable of fabricating high-resolution 3D multilayer neuronal networks using low-viscosity natural hydrogels with mechanical properties similar to brain tissue, and simultaneously analyzing their structural and functional connectivity.

Conventional bioprinting technology uses high-viscosity bioinks for structural stability, but this limits neuronal proliferation and neurite growth. Conversely, neural cell-friendly low-viscosity hydrogels are difficult to precisely pattern, leading to a fundamental trade-off between structural stability and biological function. The research team completed a sophisticated and stable brain-mimicking platform by combining three key technologies that enable the precise creation of brain structure with dilute gels, accurate alignment between layers, and simultaneous observation of neuronal activity.

The three core technologies are: ▲ 'Capillary Pinning Effect' technology, which enables the dilute gel (hydrogel) to adhere firmly to a stainless steel mesh (micromesh) to prevent it from flowing, thereby reproducing brain structures with six times greater precision (resolution of 500 μm or less) than conventional methods; ▲ the '3D Printing Aligner,' a cylindrical design that ensures the printed layers are precisely stacked without misalignment, guaranteeing the accurate assembly of multilayer structures and stable integration with microelectrode chips; and ▲ 'Dual-mode Analysis System' technology, which simultaneously measures electrical signals from below and observes cell activity with light (calcium imaging) from above, allowing for the simultaneous verification of the functional operation of interlayer connections through multiple methods.

< Figure 1. Platform integrating brain-structure-mimicking neural network model construction and functional measurement technology>

The research team successfully implemented a three-layered mini-brain structure using 3D printing with a fibrin hydrogel, which has elastic properties similar to those of the brain, and experimentally verified the process of actual neural cells transmitting and receiving signals within it.

Cortical neurons were placed in the upper and lower layers, while the middle layer was left empty but designed to allow neurons to penetrate and connect through it. Electrical signals were measured from the lower layer using a microsensor (electrode chip), and cell activity was observed from the upper layer using light (calcium imaging). The results showed that when electrical stimulation was applied, neural cells in both upper and lower layers responded simultaneously. When a synapse-blocking agent (synaptic blocker) was introduced, the response decreased, proving that the neural cells were genuinely connected and transmitting signals.

Professor Je-Kyun Park of KAIST explained, "This research is a joint development achievement of an integrated platform that can simultaneously reproduce the complex multilayered structure and function of brain tissue. Compared to existing technologies where signal measurement was impossible for more than 14 days, this platform maintains a stable microelectrode chip interface for over 27 days, allowing the real-time analysis of structure-function relationships. It can be utilized in various brain research fields such as neurological disease modeling, brain function research, neurotoxicity assessment, and neuroprotective drug screening in the future."

The research, in which Dr. Soo Jee Kim and Dr. Dongjo Yoon from KAIST's Department of Bio and Brain Engineering participated as co-first authors, was published online in the international journal 'Biosensors and Bioelectronics' on June 11, 2025.

※Paper: Hybrid biofabrication of multilayered 3D neuronal networks with structural and functional interlayer connectivity

※DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2025.117688

2025.07.16 View 555 -

KAIST Shows That the Brain Can Distinguish Glucose: Clues to Treat Obesity and Diabetes

<(From left)Prof. Greg S.B Suh, Dr. Jieun Kim, Dr. Shinhye Kim, Researcher Wongyo Jeong)

“How does our brain distinguish glucose from the many nutrients absorbed in the gut?” Starting with this question, a KAIST research team has demonstrated that the brain can selectively recognize specific nutrients—particularly glucose—beyond simply detecting total calorie content. This study is expected to offer a new paradigm for appetite control and the treatment of metabolic diseases.

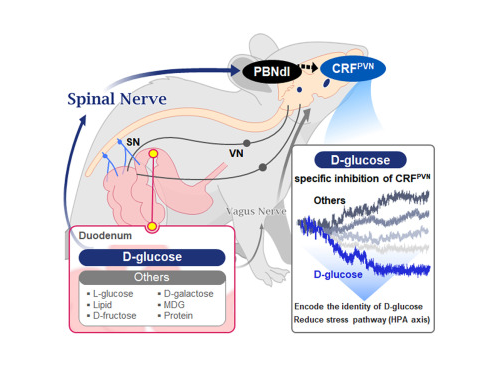

On the 9th, KAIST (President Kwang Hyung Lee) announced that Professor Greg S.B. Suh’s team in the Department of Biological Sciences, in collaboration with Professor Young-Gyun Park’s team (BarNeuro), Professor Seung-Hee Lee’s team (Department of Biological Sciences), and the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, had identified the existence of a gut-brain circuit that allows animals in a hungry state to selectively detect and prefer glucose in the gut.

Organisms derive energy from various nutrients including sugars, proteins, and fats. Previous studies have shown that total caloric information in the gut suppresses hunger neurons in the hypothalamus to regulate appetite. However, the existence of a gut-brain circuit that specifically responds to glucose and corresponding brain cells had not been demonstrated until now.

In this study, the team successfully identified a “gut-brain circuit” that senses glucose—essential for brain function—and regulates food intake behavior for required nutrients.

They further proved, for the first time, that this circuit responds within seconds to not only hunger or external stimuli but also to specific caloric nutrients directly introduced into the small intestine, particularly D-glucose, through the activity of “CRF neurons*” in the brain’s hypothalamus.

*CRF neurons: These neurons secrete corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) in the hypothalamus and are central to the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the body’s core physiological system for responding to stress. CRF neurons are known to regulate neuroendocrine balance in response to stress stimuli.

Using optogenetics to precisely track neural activity in real time, the researchers injected various nutrients—D-glucose, L-glucose, amino acids, and fats—directly into the small intestines of mice and observed the results.

They discovered that among the CRF neurons located in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN)* of the hypothalamus, only those specific to D-glucose showed selective responses. These neurons did not respond—or showed inverse reactions—to other sugars or to proteins and fats. This is the first demonstration that single neurons in the brain can guide nutrient-specific responses depending on gut nutrient influx.

*PVN (Paraventricular Nucleus): A key nucleus within the hypothalamus responsible for maintaining bodily homeostasis.

The team also revealed that glucose-sensing signals in the small intestine are transmitted via the spinal cord to the dorsolateral parabrachial nucleus (PBNdl) of the brain, and from there to CRF neurons in the PVN. In contrast, signals for amino acids and fats are transmitted to the brain through the vagus nerve, a different pathway.

In optogenetic inhibition experiments, suppressing CRF neurons in fasting mice eliminated their preference for glucose, proving that this circuit is essential for glucose-specific nutrient preference.

This study was inspired by Professor Suh’s earlier research at NYU using fruit flies, where he identified “DH44 neurons” that selectively detect glucose and sugar in the gut. Based on the hypothesis that hypothalamic neurons in mammals would show similar functional responses to glucose, the current study was launched.

To test this hypothesis, Dr. Jineun Kim (KAIST Ph.D. graduate, now at Caltech) demonstrated during her doctoral research that hungry mice preferred glucose among various intragastrically infused nutrients and that CRF neurons exhibited rapid and specific responses.

Along with Wongyo Jung (KAIST B.S. graduate, now Ph.D. student at Caltech), they modeled and experimentally confirmed the critical role of CRF neurons. Dr. Shinhye Kim, through collaboration, revealed that specific spinal neurons play a key role in conveying intestinal nutrient information to the brain.

Dr. Jineun Kim and Dr. Shinhye Kim said, “This study started from a simple but fundamental question—‘How does the brain distinguish glucose from various nutrients absorbed in the gut?’ We have shown that spinal-based gut-brain circuits play a central role in energy metabolism and homeostasis by transmitting specific gut nutrient signals to the brain.”

Professor Suh added, “By identifying a gut-brain pathway specialized for glucose, this research offers a new therapeutic target for metabolic diseases such as obesity and diabetes. Our future research will explore similar circuits for sensing other essential nutrients like amino acids and fats and their interaction mechanisms.”

Ph.D. student Jineun Kim, Dr. Shinhye Kim, and student Wongyo Jung (co-first authors) contributed to this study, which was published online in the international journal Neuron on June 20, 2025.

※ Paper Title: Encoding the glucose identity by discrete hypothalamic neurons via the gut-brain axis ※ DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2025.05.024

This study was supported by the Samsung Science & Technology Foundation, the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) Leader Research Program, the POSCO Cheongam Science Fellowship, the Asan Foundation Biomedical Science Scholarship, the Institute for Basic Science (IBS), and the KAIST KAIX program.

2025.07.09 View 741

KAIST Shows That the Brain Can Distinguish Glucose: Clues to Treat Obesity and Diabetes

<(From left)Prof. Greg S.B Suh, Dr. Jieun Kim, Dr. Shinhye Kim, Researcher Wongyo Jeong)

“How does our brain distinguish glucose from the many nutrients absorbed in the gut?” Starting with this question, a KAIST research team has demonstrated that the brain can selectively recognize specific nutrients—particularly glucose—beyond simply detecting total calorie content. This study is expected to offer a new paradigm for appetite control and the treatment of metabolic diseases.

On the 9th, KAIST (President Kwang Hyung Lee) announced that Professor Greg S.B. Suh’s team in the Department of Biological Sciences, in collaboration with Professor Young-Gyun Park’s team (BarNeuro), Professor Seung-Hee Lee’s team (Department of Biological Sciences), and the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, had identified the existence of a gut-brain circuit that allows animals in a hungry state to selectively detect and prefer glucose in the gut.

Organisms derive energy from various nutrients including sugars, proteins, and fats. Previous studies have shown that total caloric information in the gut suppresses hunger neurons in the hypothalamus to regulate appetite. However, the existence of a gut-brain circuit that specifically responds to glucose and corresponding brain cells had not been demonstrated until now.

In this study, the team successfully identified a “gut-brain circuit” that senses glucose—essential for brain function—and regulates food intake behavior for required nutrients.

They further proved, for the first time, that this circuit responds within seconds to not only hunger or external stimuli but also to specific caloric nutrients directly introduced into the small intestine, particularly D-glucose, through the activity of “CRF neurons*” in the brain’s hypothalamus.

*CRF neurons: These neurons secrete corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) in the hypothalamus and are central to the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the body’s core physiological system for responding to stress. CRF neurons are known to regulate neuroendocrine balance in response to stress stimuli.

Using optogenetics to precisely track neural activity in real time, the researchers injected various nutrients—D-glucose, L-glucose, amino acids, and fats—directly into the small intestines of mice and observed the results.

They discovered that among the CRF neurons located in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN)* of the hypothalamus, only those specific to D-glucose showed selective responses. These neurons did not respond—or showed inverse reactions—to other sugars or to proteins and fats. This is the first demonstration that single neurons in the brain can guide nutrient-specific responses depending on gut nutrient influx.

*PVN (Paraventricular Nucleus): A key nucleus within the hypothalamus responsible for maintaining bodily homeostasis.

The team also revealed that glucose-sensing signals in the small intestine are transmitted via the spinal cord to the dorsolateral parabrachial nucleus (PBNdl) of the brain, and from there to CRF neurons in the PVN. In contrast, signals for amino acids and fats are transmitted to the brain through the vagus nerve, a different pathway.

In optogenetic inhibition experiments, suppressing CRF neurons in fasting mice eliminated their preference for glucose, proving that this circuit is essential for glucose-specific nutrient preference.

This study was inspired by Professor Suh’s earlier research at NYU using fruit flies, where he identified “DH44 neurons” that selectively detect glucose and sugar in the gut. Based on the hypothesis that hypothalamic neurons in mammals would show similar functional responses to glucose, the current study was launched.

To test this hypothesis, Dr. Jineun Kim (KAIST Ph.D. graduate, now at Caltech) demonstrated during her doctoral research that hungry mice preferred glucose among various intragastrically infused nutrients and that CRF neurons exhibited rapid and specific responses.

Along with Wongyo Jung (KAIST B.S. graduate, now Ph.D. student at Caltech), they modeled and experimentally confirmed the critical role of CRF neurons. Dr. Shinhye Kim, through collaboration, revealed that specific spinal neurons play a key role in conveying intestinal nutrient information to the brain.

Dr. Jineun Kim and Dr. Shinhye Kim said, “This study started from a simple but fundamental question—‘How does the brain distinguish glucose from various nutrients absorbed in the gut?’ We have shown that spinal-based gut-brain circuits play a central role in energy metabolism and homeostasis by transmitting specific gut nutrient signals to the brain.”

Professor Suh added, “By identifying a gut-brain pathway specialized for glucose, this research offers a new therapeutic target for metabolic diseases such as obesity and diabetes. Our future research will explore similar circuits for sensing other essential nutrients like amino acids and fats and their interaction mechanisms.”

Ph.D. student Jineun Kim, Dr. Shinhye Kim, and student Wongyo Jung (co-first authors) contributed to this study, which was published online in the international journal Neuron on June 20, 2025.

※ Paper Title: Encoding the glucose identity by discrete hypothalamic neurons via the gut-brain axis ※ DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2025.05.024

This study was supported by the Samsung Science & Technology Foundation, the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) Leader Research Program, the POSCO Cheongam Science Fellowship, the Asan Foundation Biomedical Science Scholarship, the Institute for Basic Science (IBS), and the KAIST KAIX program.

2025.07.09 View 741 -

KAIST Enhances Immunotherapy for Difficult-to-Treat Brain Tumors with Gut Microbiota

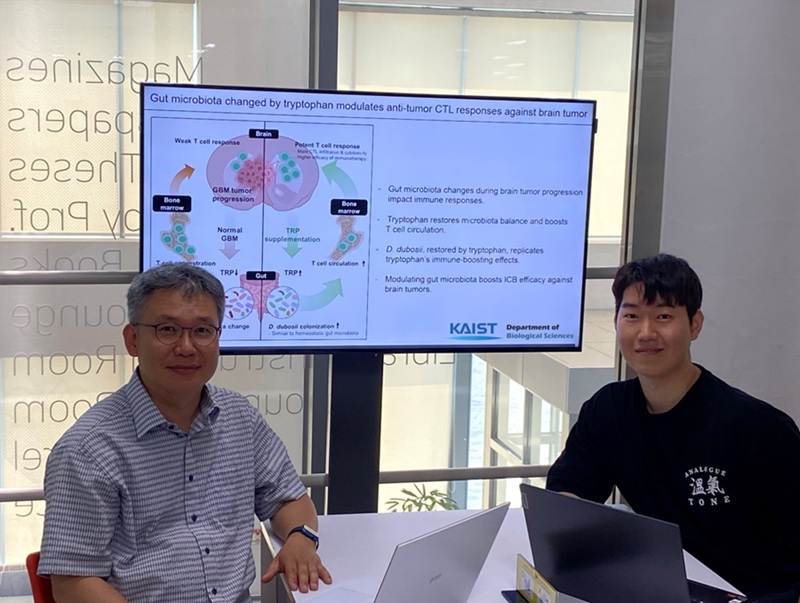

< Photo 1.(From left) Prof. Heung Kyu Lee, Department of Biological Sciences,

and Dr. Hyeon Cheol Kim>

Advanced treatments, known as immunotherapies that activate T cells—our body's immune cells—to eliminate cancer cells, have shown limited efficacy as standalone therapies for glioblastoma, the most lethal form of brain tumor. This is due to their minimal response to glioblastoma and high resistance to treatment.

Now, a KAIST research team has now demonstrated a new therapeutic strategy that can enhance the efficacy of immunotherapy for brain tumors by utilizing gut microbes and their metabolites. This also opens up possibilities for developing microbiome-based immunotherapy supplements in the future.

KAIST (President Kwang Hyung Lee) announced on July 1 that a research team led by Professor Heung Kyu Lee of the Department of Biological Sciences discovered and demonstrated a method to significantly improve the efficiency of glioblastoma immunotherapy by focusing on changes in the gut microbial ecosystem.

The research team noted that as glioblastoma progresses, the concentration of ‘tryptophan’, an important amino acid in the gut, sharply decreases, leading to changes in the gut microbial ecosystem. They discovered that by supplementing tryptophan to restore microbial diversity, specific beneficial strains activate CD8 T cells (a type of immune cell) and induce their infiltration into tumor tissues. Through a mouse model of glioblastoma, the research team confirmed that tryptophan supplementation enhanced the response of cancer-attacking T cells (especially CD8 T cells), leading to their increased migration to tumor sites such as lymph nodes and the brain.

In this process, they also revealed that ‘Duncaniella dubosii’, a beneficial commensal bacterium present in the gut, plays a crucial role. This bacterium helped T cells effectively redistribute within the body, and survival rates significantly improved when used in combination with immunotherapy (anti-PD-1).

Furthermore, it was demonstrated that even when this commensal bacterium was administered alone to germ-free mice (mice without any commensal microbes), the survival rate for glioblastoma increased. This is because the bacterium utilizes tryptophan to regulate the gut environment, and the metabolites produced in this process strengthen the ability of CD8 T cells to attack cancer cells.

Professor Heung Kyu Lee explained, "This research is a meaningful achievement, showing that even in intractable brain tumors where immune checkpoint inhibitors had no effect, a combined strategy utilizing gut microbes can significantly enhance treatment response."

Dr. Hyeon Cheol Kim of KAIST (currently a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute for Biological Sciences) participated as the first author. The research findings were published online in Cell Reports, an international journal in the life sciences, on June 26.

This research was conducted as part of the Basic Research Program and Bio & Medical Technology Development Program supported by the Ministry of Science and ICT and the National Research Foundation of Korea.

※Paper Title: Gut microbiota dysbiosis induced by brain tumor modulates the efficacy of immunotherapy

※DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2025.115825

2025.07.02 View 1391

KAIST Enhances Immunotherapy for Difficult-to-Treat Brain Tumors with Gut Microbiota

< Photo 1.(From left) Prof. Heung Kyu Lee, Department of Biological Sciences,

and Dr. Hyeon Cheol Kim>

Advanced treatments, known as immunotherapies that activate T cells—our body's immune cells—to eliminate cancer cells, have shown limited efficacy as standalone therapies for glioblastoma, the most lethal form of brain tumor. This is due to their minimal response to glioblastoma and high resistance to treatment.

Now, a KAIST research team has now demonstrated a new therapeutic strategy that can enhance the efficacy of immunotherapy for brain tumors by utilizing gut microbes and their metabolites. This also opens up possibilities for developing microbiome-based immunotherapy supplements in the future.

KAIST (President Kwang Hyung Lee) announced on July 1 that a research team led by Professor Heung Kyu Lee of the Department of Biological Sciences discovered and demonstrated a method to significantly improve the efficiency of glioblastoma immunotherapy by focusing on changes in the gut microbial ecosystem.

The research team noted that as glioblastoma progresses, the concentration of ‘tryptophan’, an important amino acid in the gut, sharply decreases, leading to changes in the gut microbial ecosystem. They discovered that by supplementing tryptophan to restore microbial diversity, specific beneficial strains activate CD8 T cells (a type of immune cell) and induce their infiltration into tumor tissues. Through a mouse model of glioblastoma, the research team confirmed that tryptophan supplementation enhanced the response of cancer-attacking T cells (especially CD8 T cells), leading to their increased migration to tumor sites such as lymph nodes and the brain.

In this process, they also revealed that ‘Duncaniella dubosii’, a beneficial commensal bacterium present in the gut, plays a crucial role. This bacterium helped T cells effectively redistribute within the body, and survival rates significantly improved when used in combination with immunotherapy (anti-PD-1).

Furthermore, it was demonstrated that even when this commensal bacterium was administered alone to germ-free mice (mice without any commensal microbes), the survival rate for glioblastoma increased. This is because the bacterium utilizes tryptophan to regulate the gut environment, and the metabolites produced in this process strengthen the ability of CD8 T cells to attack cancer cells.

Professor Heung Kyu Lee explained, "This research is a meaningful achievement, showing that even in intractable brain tumors where immune checkpoint inhibitors had no effect, a combined strategy utilizing gut microbes can significantly enhance treatment response."

Dr. Hyeon Cheol Kim of KAIST (currently a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute for Biological Sciences) participated as the first author. The research findings were published online in Cell Reports, an international journal in the life sciences, on June 26.

This research was conducted as part of the Basic Research Program and Bio & Medical Technology Development Program supported by the Ministry of Science and ICT and the National Research Foundation of Korea.

※Paper Title: Gut microbiota dysbiosis induced by brain tumor modulates the efficacy of immunotherapy

※DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2025.115825

2025.07.02 View 1391 -

5 Biomarkers for Overcoming Colorectal Cancer Drug Resistance Identified

< Professor Kwang-Hyun Cho's Team >

KAIST researchers have identified five biomarkers that will help them address resistance to cancer-targeting therapeutics. This new treatment strategy will bring us one step closer to precision medicine for patients who showed resistance.

Colorectal cancer is one of the most common types of cancer worldwide. The number of patients has surpassed 1 million, and its five-year survival rate significantly drops to about 20 percent when metastasized. In Korea, the surge of colorectal cancer has been the highest in the last 10 years due to increasing Westernized dietary patterns and obesity. It is expected that the number and mortality rates of colorectal cancer patients will increase sharply as the nation is rapidly facing an increase in its aging population.

Recently, anticancer agents targeting only specific molecules of colon cancer cells have been developed. Unlike conventional anticancer medications, these selectively treat only specific target factors, so they can significantly reduce some of the side-effects of anticancer therapy while enhancing drug efficacy.

Cetuximab is the most well-known FDA approved anticancer medication. It is a biomarker that predicts drug reactivity and utilizes the presence of the ‘KRAS’ gene mutation. Cetuximab is prescribed to patients who don’t carry the KRAS gene mutation.

However, even in patients without the KRAS gene mutation, the response rate of Cetuximab is only about fifty percent, and there is also resistance to drugs after targeted chemotherapy. Compared with conventional chemotherapy alone, the life expectancy only lasts five months on average.

In research featured in the FEBS Journal as the cover paper for the April 7 edition, the KAIST research team led by Professor Kwang-Hyun Cho at the Department of Bio and Brain Engineering presented five additional biomarkers that could increase Cetuximab responsiveness using systems biology approach that combines genomic data analysis, mathematical modeling, and cell experiments. The experimental inhibition of newly discovered biomarkers DUSP4, ETV5, GNB5, NT5E, and PHLDA1 in colorectal cancer cells has been shown to overcome Cetuximab resistance in KRAS-normal genes. The research team confirmed that when suppressing GNB5, one of the new biomarkers, it was shown to overcome resistance to Cetuximab regardless of having a mutation in the KRAS gene.

Professor Cho said, “There has not been an example of colorectal cancer treatment involving regulation of the GNB5 gene.” He continued, “Identifying the principle of drug resistance in cancer cells through systems biology and discovering new biomarkers that could be a new molecular target to overcome drug resistance suggest real potential to actualize precision medicine.”

This study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) and funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (2017R1A2A1A17069642 and 2015M3A9A7067220).

Image 1. The cover of FEBS Journal for April 2019

2019.05.27 View 61989

5 Biomarkers for Overcoming Colorectal Cancer Drug Resistance Identified

< Professor Kwang-Hyun Cho's Team >

KAIST researchers have identified five biomarkers that will help them address resistance to cancer-targeting therapeutics. This new treatment strategy will bring us one step closer to precision medicine for patients who showed resistance.

Colorectal cancer is one of the most common types of cancer worldwide. The number of patients has surpassed 1 million, and its five-year survival rate significantly drops to about 20 percent when metastasized. In Korea, the surge of colorectal cancer has been the highest in the last 10 years due to increasing Westernized dietary patterns and obesity. It is expected that the number and mortality rates of colorectal cancer patients will increase sharply as the nation is rapidly facing an increase in its aging population.

Recently, anticancer agents targeting only specific molecules of colon cancer cells have been developed. Unlike conventional anticancer medications, these selectively treat only specific target factors, so they can significantly reduce some of the side-effects of anticancer therapy while enhancing drug efficacy.

Cetuximab is the most well-known FDA approved anticancer medication. It is a biomarker that predicts drug reactivity and utilizes the presence of the ‘KRAS’ gene mutation. Cetuximab is prescribed to patients who don’t carry the KRAS gene mutation.

However, even in patients without the KRAS gene mutation, the response rate of Cetuximab is only about fifty percent, and there is also resistance to drugs after targeted chemotherapy. Compared with conventional chemotherapy alone, the life expectancy only lasts five months on average.

In research featured in the FEBS Journal as the cover paper for the April 7 edition, the KAIST research team led by Professor Kwang-Hyun Cho at the Department of Bio and Brain Engineering presented five additional biomarkers that could increase Cetuximab responsiveness using systems biology approach that combines genomic data analysis, mathematical modeling, and cell experiments. The experimental inhibition of newly discovered biomarkers DUSP4, ETV5, GNB5, NT5E, and PHLDA1 in colorectal cancer cells has been shown to overcome Cetuximab resistance in KRAS-normal genes. The research team confirmed that when suppressing GNB5, one of the new biomarkers, it was shown to overcome resistance to Cetuximab regardless of having a mutation in the KRAS gene.

Professor Cho said, “There has not been an example of colorectal cancer treatment involving regulation of the GNB5 gene.” He continued, “Identifying the principle of drug resistance in cancer cells through systems biology and discovering new biomarkers that could be a new molecular target to overcome drug resistance suggest real potential to actualize precision medicine.”

This study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) and funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (2017R1A2A1A17069642 and 2015M3A9A7067220).

Image 1. The cover of FEBS Journal for April 2019

2019.05.27 View 61989 -

KAIST Unveils the Hidden Control Architecture of Brain Networks

(Professor Kwang-Hyun Cho and his team)

A KAIST research team identified the intrinsic control architecture of brain networks. The control properties will contribute to providing a fundamental basis for the exogenous control of brain networks and, therefore, has broad implications in cognitive and clinical neuroscience.

Although efficiency and robustness are often regarded as having a trade-off relationship, the human brain usually exhibits both attributes when it performs complex cognitive functions. Such optimality must be rooted in a specific coordinated control of interconnected brain regions, but the understanding of the intrinsic control architecture of brain networks is lacking.

Professor Kwang-Hyun Cho from the Department of Bio and Brain Engineering and his team investigated the intrinsic control architecture of brain networks. They employed an interdisciplinary approach that spans connectomics, neuroscience, control engineering, network science, and systems biology to examine the structural brain networks of various species and compared them with the control architecture of other biological networks, as well as man-made ones, such as social, infrastructural and technological networks.

In particular, the team reconstructed the structural brain networks of 100 healthy human adults by performing brain parcellation and tractography with structural and diffusion imaging data obtained from the Human Connectome Project database of the US National Institutes of Health.

The team developed a framework for analyzing the control architecture of brain networks based on the minimum dominating set (MDSet), which refers to a minimal subset of nodes (MD-nodes) that control the remaining nodes with a one-step direct interaction. MD-nodes play a crucial role in various complex networks including biomolecular networks, but they have not been investigated in brain networks.

By exploring and comparing the structural principles underlying the composition of MDSets of various complex networks, the team delineated their distinct control architectures. Interestingly, the team found that the proportion of MDSets in brain networks is remarkably small compared to those of other complex networks. This finding implies that brain networks may have been optimized for minimizing the cost required for controlling networks. Furthermore, the team found that the MDSets of brain networks are not solely determined by the degree of nodes, but rather strategically placed to form a particular control architecture.

Consequently, the team revealed the hidden control architecture of brain networks, namely, the distributed and overlapping control architecture that is distinct from other complex networks. The team found that such a particular control architecture brings about robustness against targeted attacks (i.e., preferential attacks on high-degree nodes) which might be a fundamental basis of robust brain functions against preferential damage of high-degree nodes (i.e., brain regions).

Moreover, the team found that the particular control architecture of brain networks also enables high efficiency in switching from one network state, defined by a set of node activities, to another – a capability that is crucial for traversing diverse cognitive states.

Professor Cho said, “This study is the first attempt to make a quantitative comparison between brain networks and other real-world complex networks. Understanding of intrinsic control architecture underlying brain networks may enable the development of optimal interventions for therapeutic purposes or cognitive enhancement.”

This research, led by Byeongwook Lee, Uiryong Kang and Hongjun Chang, was published in iScience (10.1016/j.isci.2019.02.017) on March 29, 2019.

Figure 1. Schematic of identification of control architecture of brain networks.

Figure 2. Identified control architectures of brain networks and other real-world complex networks.

2019.04.23 View 39554

KAIST Unveils the Hidden Control Architecture of Brain Networks

(Professor Kwang-Hyun Cho and his team)

A KAIST research team identified the intrinsic control architecture of brain networks. The control properties will contribute to providing a fundamental basis for the exogenous control of brain networks and, therefore, has broad implications in cognitive and clinical neuroscience.

Although efficiency and robustness are often regarded as having a trade-off relationship, the human brain usually exhibits both attributes when it performs complex cognitive functions. Such optimality must be rooted in a specific coordinated control of interconnected brain regions, but the understanding of the intrinsic control architecture of brain networks is lacking.

Professor Kwang-Hyun Cho from the Department of Bio and Brain Engineering and his team investigated the intrinsic control architecture of brain networks. They employed an interdisciplinary approach that spans connectomics, neuroscience, control engineering, network science, and systems biology to examine the structural brain networks of various species and compared them with the control architecture of other biological networks, as well as man-made ones, such as social, infrastructural and technological networks.

In particular, the team reconstructed the structural brain networks of 100 healthy human adults by performing brain parcellation and tractography with structural and diffusion imaging data obtained from the Human Connectome Project database of the US National Institutes of Health.

The team developed a framework for analyzing the control architecture of brain networks based on the minimum dominating set (MDSet), which refers to a minimal subset of nodes (MD-nodes) that control the remaining nodes with a one-step direct interaction. MD-nodes play a crucial role in various complex networks including biomolecular networks, but they have not been investigated in brain networks.

By exploring and comparing the structural principles underlying the composition of MDSets of various complex networks, the team delineated their distinct control architectures. Interestingly, the team found that the proportion of MDSets in brain networks is remarkably small compared to those of other complex networks. This finding implies that brain networks may have been optimized for minimizing the cost required for controlling networks. Furthermore, the team found that the MDSets of brain networks are not solely determined by the degree of nodes, but rather strategically placed to form a particular control architecture.

Consequently, the team revealed the hidden control architecture of brain networks, namely, the distributed and overlapping control architecture that is distinct from other complex networks. The team found that such a particular control architecture brings about robustness against targeted attacks (i.e., preferential attacks on high-degree nodes) which might be a fundamental basis of robust brain functions against preferential damage of high-degree nodes (i.e., brain regions).

Moreover, the team found that the particular control architecture of brain networks also enables high efficiency in switching from one network state, defined by a set of node activities, to another – a capability that is crucial for traversing diverse cognitive states.

Professor Cho said, “This study is the first attempt to make a quantitative comparison between brain networks and other real-world complex networks. Understanding of intrinsic control architecture underlying brain networks may enable the development of optimal interventions for therapeutic purposes or cognitive enhancement.”

This research, led by Byeongwook Lee, Uiryong Kang and Hongjun Chang, was published in iScience (10.1016/j.isci.2019.02.017) on March 29, 2019.

Figure 1. Schematic of identification of control architecture of brain networks.

Figure 2. Identified control architectures of brain networks and other real-world complex networks.

2019.04.23 View 39554 -

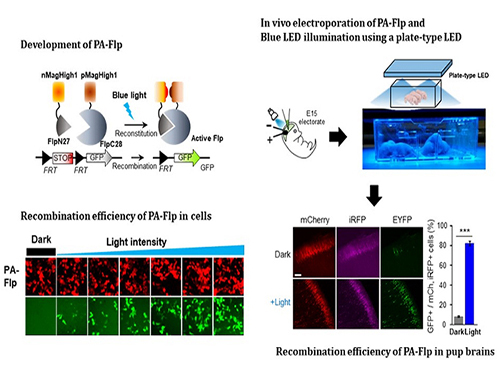

Noninvasive Light-Sensitive Recombinase for Deep Brain Genetic Manipulation

A KAIST team presented a noninvasive light-sensitive photoactivatable recombinase suitable for genetic manipulation in vivo. The highly light-sensitive property of photoactivatable Flp recombinase will be ideal for controlling genetic manipulation in deep mouse brain regions by illumination with a noninvasive light-emitting diode. This easy-to-use optogenetic module made by Professor Won Do Heo and his team will provide a side-effect free and expandable genetic manipulation tool for neuroscience research.

Spatiotemporal control of gene expression has been acclaimed as a valuable strategy for identifying functions of genes with complex neural circuits. Studies of complex brain functions require highly sophisticated and robust technologies that enable specific labeling and rapid genetic modification in live animals. A number of approaches for controlling the activity of proteins or expression of genes in a spatiotemporal manner using light, small molecules, hormones, and peptides have been developed for manipulating intact circuits or functions.

Among them, recombination-employing, chemically inducible systems are the most commonly used in vivo gene-modification systems. Other approaches include selective or conditional Cre-activation systems within subsets of green fluorescent protein-expressing cells or dual-promoter-driven intersectional populations of cells.

However, these methods are limited by the considerable time and effort required to establish knock-in mouse lines and by constraints on spatiotemporal control, which relies on a limited set of available genetic promoters and transgenic mouse resources.

Beyond these constraints, optogenetic approaches allow the activity of genetically defined neurons in the mouse brain to be controlled with high spatiotemporal resolution. However, an optogenetic module for gene-manipulation capable of revealing the spatiotemporal functions of specific target genes in the mouse brain has remained a challenge.

In the study published at Nature Communication on Jan. 18, the team featured photoactivatable Flp recombinase by searching out split sites of Flp recombinase that were not previously identified, being capable of reconstitution to be active. The team validated the highly light-sensitive, efficient performance of photoactivatable Flp recombinase through precise light targeting by showing transgene expression within anatomically confined mouse brain regions.

The concept of local genetic labeling presented here suggests a new approach for genetically identifying subpopulations of cells defined by the spatial and temporal characteristics of light delivery. To date, an optogenetic module for gene-manipulation capable of revealing spatiotemporal functions of specific target genes in the mouse brain has remained out of reach and no such light-inducible Flp system has been developed. Accordingly, the team sought to develop a photoactivatable Flp recombinase that takes full advantage of the high spatiotemporal control offered by light stimulation.

This activation through noninvasive light illumination deep inside the brain is advantageous in that it avoids chemical or optic fiber implantation-mediated side effects, such as off-target cytotoxicity or physical lesions that might influence animal physiology or behaviors. The technique provides expandable utilities for transgene expression systems upon Flp recombinase activity in vivo, by designing a viral vector for minimal leaky expression influenced by viral nascent promoters.

The team demonstrated the utility of PA-Flp as a noninvasive in vivo optogenetic manipulation tool for use in the mouse brain, even applicable for deep brain structures as it can reach the hippocampus or medial septum using external LED light illumination.

The study is the result of five years of research by Professor Heo, who has led the bio-imaging and optogenetics fields by developing his own bio-imaging and optogenetics technologies. “It will be a great advantage to control specific gene expression desired by LEDs with little physical and chemical stimulation that can affect the physiological phenomenon in living animals,” he explained.

2019.01.22 View 8513

Noninvasive Light-Sensitive Recombinase for Deep Brain Genetic Manipulation

A KAIST team presented a noninvasive light-sensitive photoactivatable recombinase suitable for genetic manipulation in vivo. The highly light-sensitive property of photoactivatable Flp recombinase will be ideal for controlling genetic manipulation in deep mouse brain regions by illumination with a noninvasive light-emitting diode. This easy-to-use optogenetic module made by Professor Won Do Heo and his team will provide a side-effect free and expandable genetic manipulation tool for neuroscience research.

Spatiotemporal control of gene expression has been acclaimed as a valuable strategy for identifying functions of genes with complex neural circuits. Studies of complex brain functions require highly sophisticated and robust technologies that enable specific labeling and rapid genetic modification in live animals. A number of approaches for controlling the activity of proteins or expression of genes in a spatiotemporal manner using light, small molecules, hormones, and peptides have been developed for manipulating intact circuits or functions.

Among them, recombination-employing, chemically inducible systems are the most commonly used in vivo gene-modification systems. Other approaches include selective or conditional Cre-activation systems within subsets of green fluorescent protein-expressing cells or dual-promoter-driven intersectional populations of cells.

However, these methods are limited by the considerable time and effort required to establish knock-in mouse lines and by constraints on spatiotemporal control, which relies on a limited set of available genetic promoters and transgenic mouse resources.

Beyond these constraints, optogenetic approaches allow the activity of genetically defined neurons in the mouse brain to be controlled with high spatiotemporal resolution. However, an optogenetic module for gene-manipulation capable of revealing the spatiotemporal functions of specific target genes in the mouse brain has remained a challenge.

In the study published at Nature Communication on Jan. 18, the team featured photoactivatable Flp recombinase by searching out split sites of Flp recombinase that were not previously identified, being capable of reconstitution to be active. The team validated the highly light-sensitive, efficient performance of photoactivatable Flp recombinase through precise light targeting by showing transgene expression within anatomically confined mouse brain regions.

The concept of local genetic labeling presented here suggests a new approach for genetically identifying subpopulations of cells defined by the spatial and temporal characteristics of light delivery. To date, an optogenetic module for gene-manipulation capable of revealing spatiotemporal functions of specific target genes in the mouse brain has remained out of reach and no such light-inducible Flp system has been developed. Accordingly, the team sought to develop a photoactivatable Flp recombinase that takes full advantage of the high spatiotemporal control offered by light stimulation.

This activation through noninvasive light illumination deep inside the brain is advantageous in that it avoids chemical or optic fiber implantation-mediated side effects, such as off-target cytotoxicity or physical lesions that might influence animal physiology or behaviors. The technique provides expandable utilities for transgene expression systems upon Flp recombinase activity in vivo, by designing a viral vector for minimal leaky expression influenced by viral nascent promoters.

The team demonstrated the utility of PA-Flp as a noninvasive in vivo optogenetic manipulation tool for use in the mouse brain, even applicable for deep brain structures as it can reach the hippocampus or medial septum using external LED light illumination.

The study is the result of five years of research by Professor Heo, who has led the bio-imaging and optogenetics fields by developing his own bio-imaging and optogenetics technologies. “It will be a great advantage to control specific gene expression desired by LEDs with little physical and chemical stimulation that can affect the physiological phenomenon in living animals,” he explained.

2019.01.22 View 8513 -

Ultrathin Digital Camera Inspired by Xenos Peckii Eyes

(Professor Ki-Hun Jeong from the Department of Bio and Brain Engineering)

The visual system of Xenos peckii, an endoparasite of paper wasps, demonstrates distinct benefits for high sensitivity and high resolution, differing from the compound eyes of most insects. Taking their unique features, a KAIST team developed an ultrathin digital camera that emulates the unique eyes of Xenos peckii.

The ultrathin digital camera offers a wide field of view and high resolution in a slimmer body compared to existing imaging systems. It is expected to support various applications, such as monitoring equipment, medical imaging devices, and mobile imaging systems.

Professor Ki-Hun Jeong from the Department of Bio and Brain Engineering and his team are known for mimicking biological visual organs. The team’s past research includes an LED lens based on the abdominal segments of fireflies and biologically inspired anti-reflective structures.

Recently, the demand for ultrathin digital cameras has increased, due to the miniaturization of electronic and optical devices. However, most camera modules use multiple lenses along the optical axis to compensate for optical aberrations, resulting in a larger volume as well as a thicker total track length of digital cameras. Resolution and sensitivity would be compromised if these modules were to be simply reduced in size and thickness.

To address this issue, the team have developed micro-optical components, inspired from the visual system of Xenos peckii, and combined them with a CMOS (complementary metal oxide semiconductor) image sensor to achieve an ultrathin digital camera.

This new camera, measuring less than 2mm in thickness, emulates the eyes of Xenos peckii by using dozens of microprism arrays and microlens arrays. A microprism and microlens pair form a channel and the light-absorbing medium between the channels reduces optical crosstalk. Each channel captures the partial image at slightly different orientation, and the retrieved partial images are combined into a single image, thereby ensuring a wide field of view and high resolution.

Professor Jeong said, “We have proposed a novel method of fabricating an ultrathin camera. As the first insect-inspired, ultrathin camera that integrates a microcamera on a conventional CMOS image sensor array, our study will have a significant impact in optics and related fields.”

This research, led by PhD candidates Dongmin Keum and Kyung-Won Jang, was published in Light: Science & Applications on October 24, 2018.

Figure 1. Natural Xenos peckii eye and the biological inspiration for the ultrathin digital camera (Light: Science & Applications 2018)

Figure 2. Optical images captured by the bioinspired ultrathin digital camera (Light: Science & Applications 2018)

2018.12.31 View 9974

Ultrathin Digital Camera Inspired by Xenos Peckii Eyes

(Professor Ki-Hun Jeong from the Department of Bio and Brain Engineering)

The visual system of Xenos peckii, an endoparasite of paper wasps, demonstrates distinct benefits for high sensitivity and high resolution, differing from the compound eyes of most insects. Taking their unique features, a KAIST team developed an ultrathin digital camera that emulates the unique eyes of Xenos peckii.

The ultrathin digital camera offers a wide field of view and high resolution in a slimmer body compared to existing imaging systems. It is expected to support various applications, such as monitoring equipment, medical imaging devices, and mobile imaging systems.

Professor Ki-Hun Jeong from the Department of Bio and Brain Engineering and his team are known for mimicking biological visual organs. The team’s past research includes an LED lens based on the abdominal segments of fireflies and biologically inspired anti-reflective structures.

Recently, the demand for ultrathin digital cameras has increased, due to the miniaturization of electronic and optical devices. However, most camera modules use multiple lenses along the optical axis to compensate for optical aberrations, resulting in a larger volume as well as a thicker total track length of digital cameras. Resolution and sensitivity would be compromised if these modules were to be simply reduced in size and thickness.

To address this issue, the team have developed micro-optical components, inspired from the visual system of Xenos peckii, and combined them with a CMOS (complementary metal oxide semiconductor) image sensor to achieve an ultrathin digital camera.

This new camera, measuring less than 2mm in thickness, emulates the eyes of Xenos peckii by using dozens of microprism arrays and microlens arrays. A microprism and microlens pair form a channel and the light-absorbing medium between the channels reduces optical crosstalk. Each channel captures the partial image at slightly different orientation, and the retrieved partial images are combined into a single image, thereby ensuring a wide field of view and high resolution.

Professor Jeong said, “We have proposed a novel method of fabricating an ultrathin camera. As the first insect-inspired, ultrathin camera that integrates a microcamera on a conventional CMOS image sensor array, our study will have a significant impact in optics and related fields.”

This research, led by PhD candidates Dongmin Keum and Kyung-Won Jang, was published in Light: Science & Applications on October 24, 2018.

Figure 1. Natural Xenos peckii eye and the biological inspiration for the ultrathin digital camera (Light: Science & Applications 2018)

Figure 2. Optical images captured by the bioinspired ultrathin digital camera (Light: Science & Applications 2018)

2018.12.31 View 9974 -

Skin Hardness to Estimate Better Human Thermal Status

(Professor Young-Ho Cho and Researcher Sunghyun Yoon)

Under the same temperature and humidity, human thermal status may vary due to individual body constitution and climatic environment. A KAIST research team previously developed a wearable sweat rate sensor for human thermal comfort monitoring. Furthering the development, this time they proposed skin hardness as an additional, independent physiological sign to estimate human thermal status more accurately. This novel approach can be applied to developing systems incorporating human-machine interaction, which requires accurate information about human thermal status.

Professor Young-Ho Cho and his team from the Department of Bio and Brain Engineering had previously studied skin temperature and sweat rate to determine human thermal comfort, and developed a watch-type sweat rate sensor that accurately and steadily detects thermal comfort last February (title: Wearable Sweat Rate Sensors for Human Thermal Comfort Monitoring ).

However, skin temperature and sweat rate are still not enough to estimate exact human thermal comfort. Hence, an additional indicator is required for enhancing the accuracy and reliability of the estimation and the team selected skin hardness. When people feel hot or cold, arrector pili muscles connected to hair follicles contract and expand, and skin hardness comes from this contraction and relaxation of the muscles. Based on the phenomenon of changing skin hardness, the team proposed skin hardness as a new indicator for measuring human thermal sensation.

With this new estimation model using three physiological signs for estimating human thermal status, the team conducted human experiments and verified that skin hardness is effective and independent from the two conventional physiological signs. Adding skin hardness to the conventional model can reduce errors by 23.5%, which makes its estimation more reliable.

The team will develop a sensor that detects skin hardness and applies it to cognitive air-conditioning and heating systems that better interact with humans than existing systems.

Professor Cho said, “Introducing this new indicator, skin hardness, elevates the reliability of measuring human thermal comfort regardless of individual body constitution and climatic environment. Based on this method, we can develop a personalized air conditioning and heating system that will allow affective interaction between humans and machines by sharing both physical and mental health conditions and emotions.”

This research, led by researchers Sunghyun Yoon and Jai Kyoung Sim, was published in Scientific Reports, Vol.8, Article No.12027 on August 13, 2018. (pp.1-6)

Figure 1. Measuring human thermal status through skin hardness

Figure 2. The instrument used for measuring human thermal status through skin hardness

2018.10.17 View 7526

Skin Hardness to Estimate Better Human Thermal Status

(Professor Young-Ho Cho and Researcher Sunghyun Yoon)

Under the same temperature and humidity, human thermal status may vary due to individual body constitution and climatic environment. A KAIST research team previously developed a wearable sweat rate sensor for human thermal comfort monitoring. Furthering the development, this time they proposed skin hardness as an additional, independent physiological sign to estimate human thermal status more accurately. This novel approach can be applied to developing systems incorporating human-machine interaction, which requires accurate information about human thermal status.

Professor Young-Ho Cho and his team from the Department of Bio and Brain Engineering had previously studied skin temperature and sweat rate to determine human thermal comfort, and developed a watch-type sweat rate sensor that accurately and steadily detects thermal comfort last February (title: Wearable Sweat Rate Sensors for Human Thermal Comfort Monitoring ).

However, skin temperature and sweat rate are still not enough to estimate exact human thermal comfort. Hence, an additional indicator is required for enhancing the accuracy and reliability of the estimation and the team selected skin hardness. When people feel hot or cold, arrector pili muscles connected to hair follicles contract and expand, and skin hardness comes from this contraction and relaxation of the muscles. Based on the phenomenon of changing skin hardness, the team proposed skin hardness as a new indicator for measuring human thermal sensation.

With this new estimation model using three physiological signs for estimating human thermal status, the team conducted human experiments and verified that skin hardness is effective and independent from the two conventional physiological signs. Adding skin hardness to the conventional model can reduce errors by 23.5%, which makes its estimation more reliable.

The team will develop a sensor that detects skin hardness and applies it to cognitive air-conditioning and heating systems that better interact with humans than existing systems.

Professor Cho said, “Introducing this new indicator, skin hardness, elevates the reliability of measuring human thermal comfort regardless of individual body constitution and climatic environment. Based on this method, we can develop a personalized air conditioning and heating system that will allow affective interaction between humans and machines by sharing both physical and mental health conditions and emotions.”

This research, led by researchers Sunghyun Yoon and Jai Kyoung Sim, was published in Scientific Reports, Vol.8, Article No.12027 on August 13, 2018. (pp.1-6)