Nature

-

Gut Hormone Triggers Craving for More Proteins

- Revelations from a fly study could improve our understanding of protein malnutrition in humans. -

A new study led by KAIST researchers using fruit flies reveals how protein deficiency in the diet triggers cross talk between the gut and brain to induce a desire to eat foods rich in proteins or essential amino acids. This finding reported in the May 5 issue of Nature can lead to a better understanding of malnutrition in humans.

“All organisms require a balanced intake of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats for their well being,” explained KAIST neuroscientist and professor Greg Seong-Bae Suh. “Taking in sufficient calories alone won’t do the job, as it can still lead to severe forms of malnutrition including kwashiorkor, if the diet does not include enough proteins,” he added.

Scientists already knew that inadequate protein intake in organisms causes a preferential choice of foods rich in proteins or essential amino acids but they didn’t know precisely how this happens. A group of researchers led by Professor Suh at KAIST and Professor Won-Jae Lee at Seoul National University (SNU) investigated this process in flies by examining the effects of different genes on food preference following protein deprivation.

The group found that protein deprivation triggered the release of a gut hormone called neuropeptide CNMamide (CNMa) from a specific population of enterocytes - the intestine lining cells. Until now, scientists have known that enterocytes release digestive enzymes into the intestine to help digest and absorb nutrients in the gut. “Our study showed that enterocytes have a more complex role than we previously thought,” said Professor Suh.

Enterocytes respond to protein deprivation by releasing CNMa that conveys the nutrient status in the gut to the CNMa receptors on nerve cells in the brain. This then triggers a desire to eat foods containing essential amino acids.

Interestingly, the KAIST-SNU team also found that the microbiome - Acetobacter bacteria - present in the gut produces amino acids that can compensate for mild protein deficit in the diet. This basal level of amino acids provided by the microbiome modifies CNMa release and tempers the flies’ compensatory desire to ingest more proteins.

The research team was able to further clarify two signalling pathways that respond to protein loss from the diet and ultimately produce the CNMa hormone in these specific enterocytes.

The team said that further studies are still needed to understand how CNMa communicates with its receptors in the brain, and whether this happens by directly activating nerve cells that link the gut to the brain or by indirectly activating the brain through blood circulation. Their research could provide insights into the understanding of similar process in mammals including humans.

“We chose to investigate a simple organism, the fly, which would make it easier for us to identify and characterize key nutrient sensors. Because all organisms have cravings for needed nutrients, the nutrient sensors and their pathways we identified in flies would also be relevant to those in mammals. We believe that this research will greatly advance our understanding of the causes of metabolic disease and eating-related disorders,” Professor Suh added.

This work was supported by the Samsung Science and Technology Foundation (SSTF) and the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea.

Publication:

Kim, B., et al. (2021) Response of the Drosophila microbiome– gut–brain axis to amino acid deficit. Nature. Available online at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03522-2

Profile:

Greg Seong-Bae Suh, Ph.D

Associate Professor

seongbaesuh@kaist.ac.krLab of Neural Interoception

https://www.suhlab-neuralinteroception.kaist.ac.kr/Department of Biological Sciences

https://bio.kaist.ac.kr/

Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST)

https:/kaist.ac.kr/en/

Daejeon 34141, Korea

(END)

2021.05.17 View 9390

Gut Hormone Triggers Craving for More Proteins

- Revelations from a fly study could improve our understanding of protein malnutrition in humans. -

A new study led by KAIST researchers using fruit flies reveals how protein deficiency in the diet triggers cross talk between the gut and brain to induce a desire to eat foods rich in proteins or essential amino acids. This finding reported in the May 5 issue of Nature can lead to a better understanding of malnutrition in humans.

“All organisms require a balanced intake of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats for their well being,” explained KAIST neuroscientist and professor Greg Seong-Bae Suh. “Taking in sufficient calories alone won’t do the job, as it can still lead to severe forms of malnutrition including kwashiorkor, if the diet does not include enough proteins,” he added.

Scientists already knew that inadequate protein intake in organisms causes a preferential choice of foods rich in proteins or essential amino acids but they didn’t know precisely how this happens. A group of researchers led by Professor Suh at KAIST and Professor Won-Jae Lee at Seoul National University (SNU) investigated this process in flies by examining the effects of different genes on food preference following protein deprivation.

The group found that protein deprivation triggered the release of a gut hormone called neuropeptide CNMamide (CNMa) from a specific population of enterocytes - the intestine lining cells. Until now, scientists have known that enterocytes release digestive enzymes into the intestine to help digest and absorb nutrients in the gut. “Our study showed that enterocytes have a more complex role than we previously thought,” said Professor Suh.

Enterocytes respond to protein deprivation by releasing CNMa that conveys the nutrient status in the gut to the CNMa receptors on nerve cells in the brain. This then triggers a desire to eat foods containing essential amino acids.

Interestingly, the KAIST-SNU team also found that the microbiome - Acetobacter bacteria - present in the gut produces amino acids that can compensate for mild protein deficit in the diet. This basal level of amino acids provided by the microbiome modifies CNMa release and tempers the flies’ compensatory desire to ingest more proteins.

The research team was able to further clarify two signalling pathways that respond to protein loss from the diet and ultimately produce the CNMa hormone in these specific enterocytes.

The team said that further studies are still needed to understand how CNMa communicates with its receptors in the brain, and whether this happens by directly activating nerve cells that link the gut to the brain or by indirectly activating the brain through blood circulation. Their research could provide insights into the understanding of similar process in mammals including humans.

“We chose to investigate a simple organism, the fly, which would make it easier for us to identify and characterize key nutrient sensors. Because all organisms have cravings for needed nutrients, the nutrient sensors and their pathways we identified in flies would also be relevant to those in mammals. We believe that this research will greatly advance our understanding of the causes of metabolic disease and eating-related disorders,” Professor Suh added.

This work was supported by the Samsung Science and Technology Foundation (SSTF) and the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea.

Publication:

Kim, B., et al. (2021) Response of the Drosophila microbiome– gut–brain axis to amino acid deficit. Nature. Available online at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03522-2

Profile:

Greg Seong-Bae Suh, Ph.D

Associate Professor

seongbaesuh@kaist.ac.krLab of Neural Interoception

https://www.suhlab-neuralinteroception.kaist.ac.kr/Department of Biological Sciences

https://bio.kaist.ac.kr/

Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST)

https:/kaist.ac.kr/en/

Daejeon 34141, Korea

(END)

2021.05.17 View 9390 -

Plasma Jets Stabilize Water to Splash Less

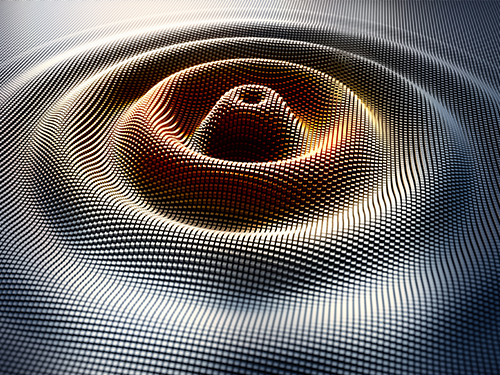

< High-speed shadowgraph movie of water surface deformations induced by plasma impingement. >

A study by KAIST researchers revealed that an ionized gas jet blowing onto water, also known as a ‘plasma jet’, produces a more stable interaction with the water’s surface compared to a neutral gas jet. This finding reported in the April 1 issue of Nature will help improve the scientific understanding of plasma-liquid interactions and their practical applications in a wide range of industrial fields in which fluid control technology is used, including biomedical engineering, chemical production, and agriculture and food engineering.

Gas jets can create dimple-like depressions in liquid surfaces, and this phenomenon is familiar to anyone who has seen the cavity produced by blowing air through a straw directly above a cup of juice. As the speed of the gas jet increases, the cavity becomes unstable and starts bubbling and splashing.

“Understanding the physical properties of interactions between gases and liquids is crucial for many natural and industrial processes, such as the wind blowing over the surface of the ocean, or steelmaking methods that involve blowing oxygen over the top of molten iron,” explained Professor Wonho Choe, a physicist from KAIST and the corresponding author of the study.

However, despite its scientific and practical importance, little is known about how gas-blown liquid cavities become deformed and destabilized.

In this study, a group of KAIST physicists led by Professor Choe and the team’s collaborators from Chonbuk National University in Korea and the Jožef Stefan Institute in Slovenia investigated what happens when an ionized gas jet, also known as a ‘plasma jet’, is blown over water. A plasma jet is created by applying high voltage to a nozzle as gas flows through it, which causes the gas to be weakly ionized and acquire freely-moving charged particles.

The research team used an optical technique combined with high-speed imaging to observe the profiles of the water surface cavities created by both neutral helium gas jets and weakly ionized helium gas jets. They also developed a computational model to mathematically explain the mechanisms behind their experimental discovery.

The researchers demonstrated for the first time that an ionized gas jet has a stabilizing effect on the water’s surface. They found that certain forces exerted by the plasma jet make the water surface cavity more stable, meaning there is less bubbling and splashing compared to the cavity created by a neutral gas jet.

Specifically, the study showed that the plasma jet consists of pulsed waves of gas ionization propagating along the water’s surface so-called ‘plasma bullets’ that exert more force than a neutral gas jet, making the cavity deeper without becoming destabilized.

“This is the first time that this phenomenon has been reported, and our group considers this as a critical step forward in our understanding of how plasma jets interact with liquid surfaces. We next plan to expand this finding through more case studies that involve diverse plasma and liquid characteristics,” said Professor Choe.

This work was supported by KAIST as part of the High-Risk and High-Return Project, the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), and the Slovenian Research Agency (ARRS).

Image Credit: Professor Wonho Choe, KAIST

Usage Restrictions: News organizations may use or redistribute these materials, with proper attribution, as part of news coverage of this paper only.

Publication: Park, S., et al. (2021) Stabilization of liquid instabilities with ionized gas jets. Nature, Vol. No. 592, Issue No. 7852, pp. 49-53. Available online at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03359-9

Profile:

Wonho Choe, Ph.D.

Professor

wchoe@kaist.ac.kr

https://gdpl.kaist.ac.kr/

Gas Discharge Physics Laboratory (GDPL)

Department of Nuclear and Quantum Engineering

Department of Physics

Impurity and Edge Plasma Research Center (IERC)

http://kaist.ac.kr/en/

Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST)

Daejeon, Republic of Korea

(END)

2021.04.01 View 12566

Plasma Jets Stabilize Water to Splash Less

< High-speed shadowgraph movie of water surface deformations induced by plasma impingement. >

A study by KAIST researchers revealed that an ionized gas jet blowing onto water, also known as a ‘plasma jet’, produces a more stable interaction with the water’s surface compared to a neutral gas jet. This finding reported in the April 1 issue of Nature will help improve the scientific understanding of plasma-liquid interactions and their practical applications in a wide range of industrial fields in which fluid control technology is used, including biomedical engineering, chemical production, and agriculture and food engineering.

Gas jets can create dimple-like depressions in liquid surfaces, and this phenomenon is familiar to anyone who has seen the cavity produced by blowing air through a straw directly above a cup of juice. As the speed of the gas jet increases, the cavity becomes unstable and starts bubbling and splashing.

“Understanding the physical properties of interactions between gases and liquids is crucial for many natural and industrial processes, such as the wind blowing over the surface of the ocean, or steelmaking methods that involve blowing oxygen over the top of molten iron,” explained Professor Wonho Choe, a physicist from KAIST and the corresponding author of the study.

However, despite its scientific and practical importance, little is known about how gas-blown liquid cavities become deformed and destabilized.

In this study, a group of KAIST physicists led by Professor Choe and the team’s collaborators from Chonbuk National University in Korea and the Jožef Stefan Institute in Slovenia investigated what happens when an ionized gas jet, also known as a ‘plasma jet’, is blown over water. A plasma jet is created by applying high voltage to a nozzle as gas flows through it, which causes the gas to be weakly ionized and acquire freely-moving charged particles.

The research team used an optical technique combined with high-speed imaging to observe the profiles of the water surface cavities created by both neutral helium gas jets and weakly ionized helium gas jets. They also developed a computational model to mathematically explain the mechanisms behind their experimental discovery.

The researchers demonstrated for the first time that an ionized gas jet has a stabilizing effect on the water’s surface. They found that certain forces exerted by the plasma jet make the water surface cavity more stable, meaning there is less bubbling and splashing compared to the cavity created by a neutral gas jet.

Specifically, the study showed that the plasma jet consists of pulsed waves of gas ionization propagating along the water’s surface so-called ‘plasma bullets’ that exert more force than a neutral gas jet, making the cavity deeper without becoming destabilized.

“This is the first time that this phenomenon has been reported, and our group considers this as a critical step forward in our understanding of how plasma jets interact with liquid surfaces. We next plan to expand this finding through more case studies that involve diverse plasma and liquid characteristics,” said Professor Choe.

This work was supported by KAIST as part of the High-Risk and High-Return Project, the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), and the Slovenian Research Agency (ARRS).

Image Credit: Professor Wonho Choe, KAIST

Usage Restrictions: News organizations may use or redistribute these materials, with proper attribution, as part of news coverage of this paper only.

Publication: Park, S., et al. (2021) Stabilization of liquid instabilities with ionized gas jets. Nature, Vol. No. 592, Issue No. 7852, pp. 49-53. Available online at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03359-9

Profile:

Wonho Choe, Ph.D.

Professor

wchoe@kaist.ac.kr

https://gdpl.kaist.ac.kr/

Gas Discharge Physics Laboratory (GDPL)

Department of Nuclear and Quantum Engineering

Department of Physics

Impurity and Edge Plasma Research Center (IERC)

http://kaist.ac.kr/en/

Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST)

Daejeon, Republic of Korea

(END)

2021.04.01 View 12566 -

Acoustic Graphene Plasmons Study Paves Way for Optoelectronic Applications

- The first images of mid-infrared optical waves compressed 1,000 times captured using a highly sensitive scattering-type scanning near-field optical microscope. -

KAIST researchers and their collaborators at home and abroad have successfully demonstrated a new methodology for direct near-field optical imaging of acoustic graphene plasmon fields. This strategy will provide a breakthrough for the practical applications of acoustic graphene plasmon platforms in next-generation, high-performance, graphene-based optoelectronic devices with enhanced light-matter interactions and lower propagation loss.

It was recently demonstrated that ‘graphene plasmons’ – collective oscillations of free electrons in graphene coupled to electromagnetic waves of light – can be used to trap and compress optical waves inside a very thin dielectric layer separating graphene from a metallic sheet. In such a configuration, graphene’s conduction electrons are “reflected” in the metal, so when the light waves “push” the electrons in graphene, their image charges in metal also start to oscillate. This new type of collective electronic oscillation mode is called ‘acoustic graphene plasmon (AGP)’.

The existence of AGP could previously be observed only via indirect methods such as far-field infrared spectroscopy and photocurrent mapping. This indirect observation was the price that researchers had to pay for the strong compression of optical waves inside nanometer-thin structures. It was believed that the intensity of electromagnetic fields outside the device was insufficient for direct near-field optical imaging of AGP.

Challenged by these limitations, three research groups combined their efforts to bring together a unique experimental technique using advanced nanofabrication methods. Their findings were published in Nature Communications on February 19.

A KAIST research team led by Professor Min Seok Jang from the School of Electrical Engineering used a highly sensitive scattering-type scanning near-field optical microscope (s-SNOM) to directly measure the optical fields of the AGP waves propagating in a nanometer-thin waveguide, visualizing thousand-fold compression of mid-infrared light for the first time.

Professor Jang and a post-doc researcher in his group, Sergey G. Menabde, successfully obtained direct images of AGP waves by taking advantage of their rapidly decaying yet always present electric field above graphene. They showed that AGPs are detectable even when most of their energy is flowing inside the dielectric below the graphene.

This became possible due to the ultra-smooth surfaces inside the nano-waveguides where plasmonic waves can propagate at longer distances. The AGP mode probed by the researchers was up to 2.3 times more confined and exhibited a 1.4 times higher figure of merit in terms of the normalized propagation length compared to the graphene surface plasmon under similar conditions.

These ultra-smooth nanostructures of the waveguides used in the experiment were created using a template-stripping method by Professor Sang-Hyun Oh and a post-doc researcher, In-Ho Lee, from the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering at the University of Minnesota.

Professor Young Hee Lee and his researchers at the Center for Integrated Nanostructure Physics (CINAP) of the Institute of Basic Science (IBS) at Sungkyunkwan University synthesized the graphene with a monocrystalline structure, and this high-quality, large-area graphene enabled low-loss plasmonic propagation.

The chemical and physical properties of many important organic molecules can be detected and evaluated by their absorption signatures in the mid-infrared spectrum. However, conventional detection methods require a large number of molecules for successful detection, whereas the ultra-compressed AGP fields can provide strong light-matter interactions at the microscopic level, thus significantly improving the detection sensitivity down to a single molecule.

Furthermore, the study conducted by Professor Jang and the team demonstrated that the mid-infrared AGPs are inherently less sensitive to losses in graphene due to their fields being mostly confined within the dielectric. The research team’s reported results suggest that AGPs could become a promising platform for electrically tunable graphene-based optoelectronic devices that typically suffer from higher absorption rates in graphene such as metasurfaces, optical switches, photovoltaics, and other optoelectronic applications operating at infrared frequencies.

Professor Jang said, “Our research revealed that the ultra-compressed electromagnetic fields of acoustic graphene plasmons can be directly accessed through near-field optical microscopy methods. I hope this realization will motivate other researchers to apply AGPs to various problems where strong light-matter interactions and lower propagation loss are needed.”

This research was primarily funded by the Samsung Research Funding & Incubation Center of Samsung Electronics. The National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF), Samsung Global Research Outreach (GRO) Program, and Institute for Basic Science of Korea (IBS) also supported the work.

Publication:

Menabde, S. G., et al. (2021) Real-space imaging of acoustic plasmons in large-area graphene grown by chemical vapor deposition. Nature Communications 12, Article No. 938. Available online at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21193-5

Profile:

Min Seok Jang, MS, PhD

Associate Professorjang.minseok@kaist.ac.krhttp://jlab.kaist.ac.kr/

Min Seok Jang Research GroupSchool of Electrical Engineering

http://kaist.ac.kr/en/Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST)Daejeon, Republic of Korea

(END)

2021.03.16 View 17148

Acoustic Graphene Plasmons Study Paves Way for Optoelectronic Applications

- The first images of mid-infrared optical waves compressed 1,000 times captured using a highly sensitive scattering-type scanning near-field optical microscope. -

KAIST researchers and their collaborators at home and abroad have successfully demonstrated a new methodology for direct near-field optical imaging of acoustic graphene plasmon fields. This strategy will provide a breakthrough for the practical applications of acoustic graphene plasmon platforms in next-generation, high-performance, graphene-based optoelectronic devices with enhanced light-matter interactions and lower propagation loss.

It was recently demonstrated that ‘graphene plasmons’ – collective oscillations of free electrons in graphene coupled to electromagnetic waves of light – can be used to trap and compress optical waves inside a very thin dielectric layer separating graphene from a metallic sheet. In such a configuration, graphene’s conduction electrons are “reflected” in the metal, so when the light waves “push” the electrons in graphene, their image charges in metal also start to oscillate. This new type of collective electronic oscillation mode is called ‘acoustic graphene plasmon (AGP)’.

The existence of AGP could previously be observed only via indirect methods such as far-field infrared spectroscopy and photocurrent mapping. This indirect observation was the price that researchers had to pay for the strong compression of optical waves inside nanometer-thin structures. It was believed that the intensity of electromagnetic fields outside the device was insufficient for direct near-field optical imaging of AGP.

Challenged by these limitations, three research groups combined their efforts to bring together a unique experimental technique using advanced nanofabrication methods. Their findings were published in Nature Communications on February 19.

A KAIST research team led by Professor Min Seok Jang from the School of Electrical Engineering used a highly sensitive scattering-type scanning near-field optical microscope (s-SNOM) to directly measure the optical fields of the AGP waves propagating in a nanometer-thin waveguide, visualizing thousand-fold compression of mid-infrared light for the first time.

Professor Jang and a post-doc researcher in his group, Sergey G. Menabde, successfully obtained direct images of AGP waves by taking advantage of their rapidly decaying yet always present electric field above graphene. They showed that AGPs are detectable even when most of their energy is flowing inside the dielectric below the graphene.

This became possible due to the ultra-smooth surfaces inside the nano-waveguides where plasmonic waves can propagate at longer distances. The AGP mode probed by the researchers was up to 2.3 times more confined and exhibited a 1.4 times higher figure of merit in terms of the normalized propagation length compared to the graphene surface plasmon under similar conditions.

These ultra-smooth nanostructures of the waveguides used in the experiment were created using a template-stripping method by Professor Sang-Hyun Oh and a post-doc researcher, In-Ho Lee, from the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering at the University of Minnesota.

Professor Young Hee Lee and his researchers at the Center for Integrated Nanostructure Physics (CINAP) of the Institute of Basic Science (IBS) at Sungkyunkwan University synthesized the graphene with a monocrystalline structure, and this high-quality, large-area graphene enabled low-loss plasmonic propagation.

The chemical and physical properties of many important organic molecules can be detected and evaluated by their absorption signatures in the mid-infrared spectrum. However, conventional detection methods require a large number of molecules for successful detection, whereas the ultra-compressed AGP fields can provide strong light-matter interactions at the microscopic level, thus significantly improving the detection sensitivity down to a single molecule.

Furthermore, the study conducted by Professor Jang and the team demonstrated that the mid-infrared AGPs are inherently less sensitive to losses in graphene due to their fields being mostly confined within the dielectric. The research team’s reported results suggest that AGPs could become a promising platform for electrically tunable graphene-based optoelectronic devices that typically suffer from higher absorption rates in graphene such as metasurfaces, optical switches, photovoltaics, and other optoelectronic applications operating at infrared frequencies.

Professor Jang said, “Our research revealed that the ultra-compressed electromagnetic fields of acoustic graphene plasmons can be directly accessed through near-field optical microscopy methods. I hope this realization will motivate other researchers to apply AGPs to various problems where strong light-matter interactions and lower propagation loss are needed.”

This research was primarily funded by the Samsung Research Funding & Incubation Center of Samsung Electronics. The National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF), Samsung Global Research Outreach (GRO) Program, and Institute for Basic Science of Korea (IBS) also supported the work.

Publication:

Menabde, S. G., et al. (2021) Real-space imaging of acoustic plasmons in large-area graphene grown by chemical vapor deposition. Nature Communications 12, Article No. 938. Available online at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21193-5

Profile:

Min Seok Jang, MS, PhD

Associate Professorjang.minseok@kaist.ac.krhttp://jlab.kaist.ac.kr/

Min Seok Jang Research GroupSchool of Electrical Engineering

http://kaist.ac.kr/en/Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST)Daejeon, Republic of Korea

(END)

2021.03.16 View 17148 -

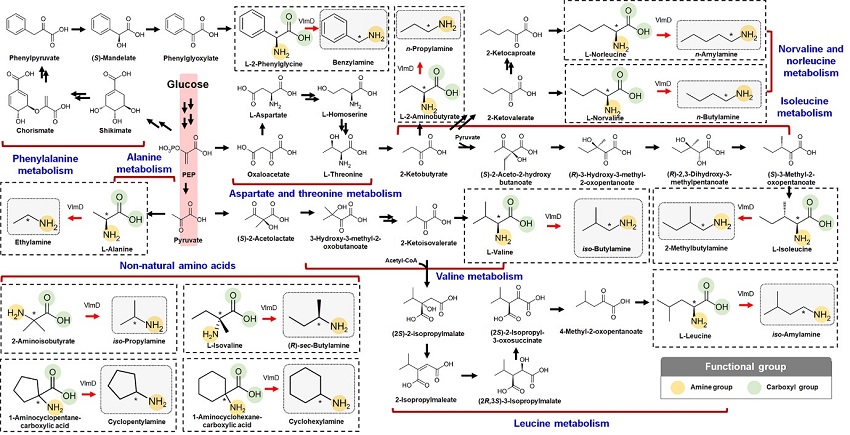

Expanding the Biosynthetic Pathway via Retrobiosynthesis

- Researchers reports a new strategy for the microbial production of multiple short-chain primary amines via retrobiosynthesis. -

KAIST metabolic engineers presented the bio-based production of multiple short-chain primary amines that have a wide range of applications in chemical industries for the first time. The research team led by Distinguished Professor Sang Yup Lee from the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering designed the novel biosynthetic pathways for short-chain primary amines by combining retrobiosynthesis and a precursor selection step.

The research team verified the newly designed pathways by confirming the in vivo production of 10 short-chain primary amines by supplying the precursors. Furthermore, the platform Escherichia coli strains were metabolically engineered to produce three proof-of-concept short-chain primary amines from glucose, demonstrating the possibility of the bio-based production of diverse short-chain primary amines from renewable resources. The research team said this study expands the strategy of systematically designing biosynthetic pathways for the production of a group of related chemicals as demonstrated by multiple short-chain primary amines as examples.

Currently, most of the industrial chemicals used in our daily lives are produced with petroleum-based products. However, there are several serious issues with the petroleum industry such as the depletion of fossil fuel reserves and environmental problems including global warming. To solve these problems, the sustainable production of industrial chemicals and materials is being explored with microorganisms as cell factories and renewable non-food biomass as raw materials for alternative to petroleum-based products. The engineering of these microorganisms has increasingly become more efficient and effective with the help of systems metabolic engineering – a practice of engineering the metabolism of a living organism toward the production of a desired metabolite. In this regard, the number of chemicals produced using biomass as a raw material has substantially increased.

Although the scope of chemicals that are producible using microorganisms continues to expand through advances in systems metabolic engineering, the biological production of short-chain primary amines has not yet been reported despite their industrial importance. Short-chain primary amines are the chemicals that have an alkyl or aryl group in the place of a hydrogen atom in ammonia with carbon chain lengths ranging from C1 to C7. Short-chain primary amines have a wide range of applications in chemical industries, for example, as a precursor for pharmaceuticals (e.g., antidiabetic and antihypertensive drugs), agrochemicals (e.g., herbicides, fungicides and insecticides), solvents, and vulcanization accelerators for rubber and plasticizers. The market size of short-chain primary amines was estimated to be more than 4 billion US dollars in 2014.

The main reason why the bio-based production of short-chain primary amines was not yet possible was due to their unknown biosynthetic pathways. Therefore, the team designed synthetic biosynthetic pathways for short-chain primary amines by combining retrobiosynthesis and a precursor selection step. The retrobiosynthesis allowed the systematic design of a biosynthetic pathway for short-chain primary amines by using a set of biochemical reaction rules that describe chemical transformation patterns between a substrate and product molecules at an atomic level.

These multiple precursors predicted for the possible biosynthesis of each short-chain primary amine were sequentially narrowed down by using the precursor selection step for efficient metabolic engineering experiments.

“Our research demonstrates the possibility of the renewable production of short-chain primary amines for the first time. We are planning to increase production efficiencies of short-chain primary amines. We believe that our study will play an important role in the development of sustainable and eco-friendly bio-based industries and the reorganization of the chemical industry, which is mandatory for solving the environmental problems threating the survival of mankind,” said Professor Lee.

This paper titled “Microbial production of multiple short-chain primary amines via retrobiosynthesis” was published in Nature Communications. This work was supported by the Technology Development Program to Solve Climate Changes on Systems Metabolic Engineering for Biorefineries from the Ministry of Science and ICT through the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea.

-Publication

Dong In Kim, Tong Un Chae, Hyun Uk Kim, Woo Dae Jang, and Sang Yup Lee. Microbial production of multiple short-chain primary amines via retrobiosynthesis. Nature Communications ( https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-020-20423-6)

-Profile

Distinguished Professor Sang Yup Lee

leesy@kaist.ac.kr

Metabolic &Biomolecular Engineering National Research Laboratory

http://mbel.kaist.ac.kr

Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering

KAIST

2021.01.14 View 14570

Expanding the Biosynthetic Pathway via Retrobiosynthesis

- Researchers reports a new strategy for the microbial production of multiple short-chain primary amines via retrobiosynthesis. -

KAIST metabolic engineers presented the bio-based production of multiple short-chain primary amines that have a wide range of applications in chemical industries for the first time. The research team led by Distinguished Professor Sang Yup Lee from the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering designed the novel biosynthetic pathways for short-chain primary amines by combining retrobiosynthesis and a precursor selection step.

The research team verified the newly designed pathways by confirming the in vivo production of 10 short-chain primary amines by supplying the precursors. Furthermore, the platform Escherichia coli strains were metabolically engineered to produce three proof-of-concept short-chain primary amines from glucose, demonstrating the possibility of the bio-based production of diverse short-chain primary amines from renewable resources. The research team said this study expands the strategy of systematically designing biosynthetic pathways for the production of a group of related chemicals as demonstrated by multiple short-chain primary amines as examples.

Currently, most of the industrial chemicals used in our daily lives are produced with petroleum-based products. However, there are several serious issues with the petroleum industry such as the depletion of fossil fuel reserves and environmental problems including global warming. To solve these problems, the sustainable production of industrial chemicals and materials is being explored with microorganisms as cell factories and renewable non-food biomass as raw materials for alternative to petroleum-based products. The engineering of these microorganisms has increasingly become more efficient and effective with the help of systems metabolic engineering – a practice of engineering the metabolism of a living organism toward the production of a desired metabolite. In this regard, the number of chemicals produced using biomass as a raw material has substantially increased.

Although the scope of chemicals that are producible using microorganisms continues to expand through advances in systems metabolic engineering, the biological production of short-chain primary amines has not yet been reported despite their industrial importance. Short-chain primary amines are the chemicals that have an alkyl or aryl group in the place of a hydrogen atom in ammonia with carbon chain lengths ranging from C1 to C7. Short-chain primary amines have a wide range of applications in chemical industries, for example, as a precursor for pharmaceuticals (e.g., antidiabetic and antihypertensive drugs), agrochemicals (e.g., herbicides, fungicides and insecticides), solvents, and vulcanization accelerators for rubber and plasticizers. The market size of short-chain primary amines was estimated to be more than 4 billion US dollars in 2014.

The main reason why the bio-based production of short-chain primary amines was not yet possible was due to their unknown biosynthetic pathways. Therefore, the team designed synthetic biosynthetic pathways for short-chain primary amines by combining retrobiosynthesis and a precursor selection step. The retrobiosynthesis allowed the systematic design of a biosynthetic pathway for short-chain primary amines by using a set of biochemical reaction rules that describe chemical transformation patterns between a substrate and product molecules at an atomic level.

These multiple precursors predicted for the possible biosynthesis of each short-chain primary amine were sequentially narrowed down by using the precursor selection step for efficient metabolic engineering experiments.

“Our research demonstrates the possibility of the renewable production of short-chain primary amines for the first time. We are planning to increase production efficiencies of short-chain primary amines. We believe that our study will play an important role in the development of sustainable and eco-friendly bio-based industries and the reorganization of the chemical industry, which is mandatory for solving the environmental problems threating the survival of mankind,” said Professor Lee.

This paper titled “Microbial production of multiple short-chain primary amines via retrobiosynthesis” was published in Nature Communications. This work was supported by the Technology Development Program to Solve Climate Changes on Systems Metabolic Engineering for Biorefineries from the Ministry of Science and ICT through the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea.

-Publication

Dong In Kim, Tong Un Chae, Hyun Uk Kim, Woo Dae Jang, and Sang Yup Lee. Microbial production of multiple short-chain primary amines via retrobiosynthesis. Nature Communications ( https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-020-20423-6)

-Profile

Distinguished Professor Sang Yup Lee

leesy@kaist.ac.kr

Metabolic &Biomolecular Engineering National Research Laboratory

http://mbel.kaist.ac.kr

Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering

KAIST

2021.01.14 View 14570 -

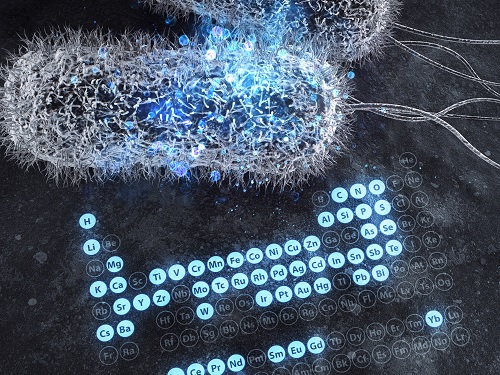

A Comprehensive Review of Biosynthesis of Inorganic Nanomaterials Using Microorganisms and Bacteriophages

There are diverse methods for producing numerous inorganic nanomaterials involving many experimental variables. Among the numerous possible matches, finding the best pair for synthesizing in an environmentally friendly way has been a longstanding challenge for researchers and industries.

A KAIST bioprocess engineering research team led by Distinguished Professor Sang Yup Lee conducted a summary of 146 biosynthesized single and multi-element inorganic nanomaterials covering 55 elements in the periodic table synthesized using wild-type and genetically engineered microorganisms. Their research highlights the diverse applications of biogenic nanomaterials and gives strategies for improving the biosynthesis of nanomaterials in terms of their producibility, crystallinity, size, and shape.

The research team described a 10-step flow chart for developing the biosynthesis of inorganic nanomaterials using microorganisms and bacteriophages. The research was published at Nature Review Chemistry as a cover and hero paper on December 3.

“We suggest general strategies for microbial nanomaterial biosynthesis via a step-by-step flow chart and give our perspectives on the future of nanomaterial biosynthesis and applications. This flow chart will serve as a general guide for those wishing to prepare biosynthetic inorganic nanomaterials using microbial cells,” explained Dr.Yoojin Choi, a co-author of this research.

Most inorganic nanomaterials are produced using physical and chemical methods and biological synthesis has been gaining more and more attention. However, conventional synthesis processes have drawbacks in terms of high energy consumption and non-environmentally friendly processes. Meanwhile, microorganisms such as microalgae, yeasts, fungi, bacteria, and even viruses can be utilized as biofactories to produce single and multi-element inorganic nanomaterials under mild conditions.

After conducting a massive survey, the research team summed up that the development of genetically engineered microorganisms with increased inorganic-ion-binding affinity, inorganic-ion-reduction ability, and nanomaterial biosynthetic efficiency has enabled the synthesis of many inorganic nanomaterials.

Among the strategies, the team introduced their analysis of a Pourbaix diagram for controlling the size and morphology of a product. The research team said this Pourbaix diagram analysis can be widely employed for biosynthesizing new nanomaterials with industrial applications.Professor Sang Yup Lee added, “This research provides extensive information and perspectives on the biosynthesis of diverse inorganic nanomaterials using microorganisms and bacteriophages and their applications. We expect that biosynthetic inorganic nanomaterials will find more diverse and innovative applications across diverse fields of science and technology.”

Dr. Choi started this research in 2018 and her interview about completing this extensive research was featured in an article at Nature Career article on December 4.

-ProfileDistinguished Professor Sang Yup Lee leesy@kaist.ac.krMetabolic &Biomolecular Engineering National Research Laboratoryhttp://mbel.kaist.ac.krDepartment of Chemical and Biomolecular EngineeringKAIST

2020.12.07 View 13477

A Comprehensive Review of Biosynthesis of Inorganic Nanomaterials Using Microorganisms and Bacteriophages

There are diverse methods for producing numerous inorganic nanomaterials involving many experimental variables. Among the numerous possible matches, finding the best pair for synthesizing in an environmentally friendly way has been a longstanding challenge for researchers and industries.

A KAIST bioprocess engineering research team led by Distinguished Professor Sang Yup Lee conducted a summary of 146 biosynthesized single and multi-element inorganic nanomaterials covering 55 elements in the periodic table synthesized using wild-type and genetically engineered microorganisms. Their research highlights the diverse applications of biogenic nanomaterials and gives strategies for improving the biosynthesis of nanomaterials in terms of their producibility, crystallinity, size, and shape.

The research team described a 10-step flow chart for developing the biosynthesis of inorganic nanomaterials using microorganisms and bacteriophages. The research was published at Nature Review Chemistry as a cover and hero paper on December 3.

“We suggest general strategies for microbial nanomaterial biosynthesis via a step-by-step flow chart and give our perspectives on the future of nanomaterial biosynthesis and applications. This flow chart will serve as a general guide for those wishing to prepare biosynthetic inorganic nanomaterials using microbial cells,” explained Dr.Yoojin Choi, a co-author of this research.

Most inorganic nanomaterials are produced using physical and chemical methods and biological synthesis has been gaining more and more attention. However, conventional synthesis processes have drawbacks in terms of high energy consumption and non-environmentally friendly processes. Meanwhile, microorganisms such as microalgae, yeasts, fungi, bacteria, and even viruses can be utilized as biofactories to produce single and multi-element inorganic nanomaterials under mild conditions.

After conducting a massive survey, the research team summed up that the development of genetically engineered microorganisms with increased inorganic-ion-binding affinity, inorganic-ion-reduction ability, and nanomaterial biosynthetic efficiency has enabled the synthesis of many inorganic nanomaterials.

Among the strategies, the team introduced their analysis of a Pourbaix diagram for controlling the size and morphology of a product. The research team said this Pourbaix diagram analysis can be widely employed for biosynthesizing new nanomaterials with industrial applications.Professor Sang Yup Lee added, “This research provides extensive information and perspectives on the biosynthesis of diverse inorganic nanomaterials using microorganisms and bacteriophages and their applications. We expect that biosynthetic inorganic nanomaterials will find more diverse and innovative applications across diverse fields of science and technology.”

Dr. Choi started this research in 2018 and her interview about completing this extensive research was featured in an article at Nature Career article on December 4.

-ProfileDistinguished Professor Sang Yup Lee leesy@kaist.ac.krMetabolic &Biomolecular Engineering National Research Laboratoryhttp://mbel.kaist.ac.krDepartment of Chemical and Biomolecular EngineeringKAIST

2020.12.07 View 13477 -

Scientist of October: Professor Jungwon Kim

Professor Jungwon Kim from the Department of Mechanical Engineering was selected as the ‘Scientist of the Month’ for October 2020 by the Ministry of Science and ICT and the National Research Foundation of Korea. Professor Kim was recognized for his contributions to expanding the horizons of the basics of precision engineering through his research on multifunctional ultrahigh-speed, high-resolution sensors. He received 10 million KRW in prize money.

Professor Kim was selected as the recipient of this award in celebration of “Measurement Day”, which commemorates October 26 as the day in which King Sejong the Great established a volume measurement system.

Professor Kim discovered that the time difference between the pulse of light created by a laser and the pulse of the current produced by a light-emitting diode was as small as 100 attoseconds (10-16 seconds). He then developed a unique multifunctional ultrahigh-speed, high-resolution Time-of-Flight (TOF) sensor that could take measurements of multiple points at the same time by sampling electric light. The sensor, with a measurement speed of 100 megahertz (100 million vibrations per second), a resolution of 180 picometers (1/5.5 billion meters), and a dynamic range of 150 decibels, overcame the limitations of both existing TOF techniques and laser interferometric techniques at the same time. The results of this research were published in Nature Photonics on February 10, 2020.

Professor Kim said, “I’d like to thank the graduate students who worked passionately with me, and KAIST for providing an environment in which I could fully focus on research. I am looking forward to the new and diverse applications in the field of machine manufacturing, such as studying the dynamic phenomena in microdevices, or taking ultraprecision measurement of shapes for advanced manufacturing.”

(END)

2020.10.15 View 15015

Scientist of October: Professor Jungwon Kim

Professor Jungwon Kim from the Department of Mechanical Engineering was selected as the ‘Scientist of the Month’ for October 2020 by the Ministry of Science and ICT and the National Research Foundation of Korea. Professor Kim was recognized for his contributions to expanding the horizons of the basics of precision engineering through his research on multifunctional ultrahigh-speed, high-resolution sensors. He received 10 million KRW in prize money.

Professor Kim was selected as the recipient of this award in celebration of “Measurement Day”, which commemorates October 26 as the day in which King Sejong the Great established a volume measurement system.

Professor Kim discovered that the time difference between the pulse of light created by a laser and the pulse of the current produced by a light-emitting diode was as small as 100 attoseconds (10-16 seconds). He then developed a unique multifunctional ultrahigh-speed, high-resolution Time-of-Flight (TOF) sensor that could take measurements of multiple points at the same time by sampling electric light. The sensor, with a measurement speed of 100 megahertz (100 million vibrations per second), a resolution of 180 picometers (1/5.5 billion meters), and a dynamic range of 150 decibels, overcame the limitations of both existing TOF techniques and laser interferometric techniques at the same time. The results of this research were published in Nature Photonics on February 10, 2020.

Professor Kim said, “I’d like to thank the graduate students who worked passionately with me, and KAIST for providing an environment in which I could fully focus on research. I am looking forward to the new and diverse applications in the field of machine manufacturing, such as studying the dynamic phenomena in microdevices, or taking ultraprecision measurement of shapes for advanced manufacturing.”

(END)

2020.10.15 View 15015 -

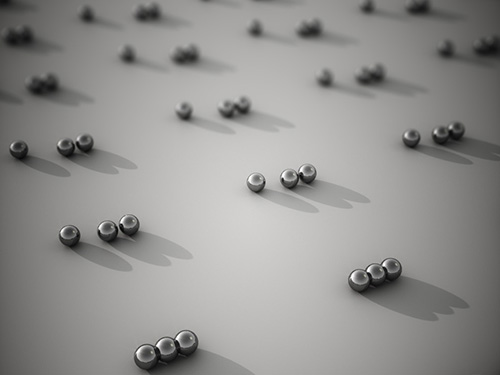

Every Moment of Ultrafast Chemical Bonding Now Captured on Film

- The emerging moment of bond formation, two separate bonding steps, and subsequent vibrational motions were visualized. -

< Emergence of molecular vibrations and the evolution to covalent bonds observed in the research. Video Credit: KEK IMSS >

A team of South Korean researchers led by Professor Hyotcherl Ihee from the Department of Chemistry at KAIST reported the direct observation of the birthing moment of chemical bonds by tracking real-time atomic positions in the molecule. Professor Ihee, who also serves as Associate Director of the Center for Nanomaterials and Chemical Reactions at the Institute for Basic Science (IBS), conducted this study in collaboration with scientists at the Institute of Materials Structure Science of High Energy Accelerator Research Organization (KEK IMSS, Japan), RIKEN (Japan), and Pohang Accelerator Laboratory (PAL, South Korea). This work was published in Nature on June 24.

Targeted cancer drugs work by striking a tight bond between cancer cell and specific molecular targets that are involved in the growth and spread of cancer. Detailed images of such chemical bonding sites or pathways can provide key information necessary for maximizing the efficacy of oncogene treatments. However, atomic movements in a molecule have never been captured in the middle of the action, not even for an extremely simple molecule such as a triatomic molecule, made of only three atoms.

Professor Ihee's group and their international collaborators finally succeeded in capturing the ongoing reaction process of the chemical bond formation in the gold trimer. "The femtosecond-resolution images revealed that such molecular events took place in two separate stages, not simultaneously as previously assumed," says Professor Ihee, the corresponding author of the study. "The atoms in the gold trimer complex atoms remain in motion even after the chemical bonding is complete. The distance between the atoms increased and decreased periodically, exhibiting the molecular vibration. These visualized molecular vibrations allowed us to name the characteristic motion of each observed vibrational mode." adds Professor Ihee.

Atoms move extremely fast at a scale of femtosecond (fs) ― quadrillionths (or millionths of a billionth) of a second. Its movement is minute in the level of angstrom equal to one ten-billionth of a meter. They are especially elusive during the transition state where reaction intermediates are transitioning from reactants to products in a flash. The KAIST-IBS research team made this experimentally challenging task possible by using femtosecond x-ray liquidography (solution scattering). This experimental technique combines laser photolysis and x-ray scattering techniques. When a laser pulse strikes the sample, X-rays scatter and initiate the chemical bond formation reaction in the gold trimer complex. Femtosecond x-ray pulses obtained from a special light source called an x-ray free-electron laser (XFEL) were used to interrogate the bond-forming process. The experiments were performed at two XFEL facilities (4th generation linear accelerator) that are PAL-XFEL in South Korea and SACLA in Japan, and this study was conducted in collaboration with researchers from KEK IMSS, PAL, RIKEN, and the Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute (JASRI).

Scattered waves from each atom interfere with each other and thus their x-ray scattering images are characterized by specific travel directions. The KAIST-IBS research team traced real-time positions of the three gold atoms over time by analyzing x-ray scattering images, which are determined by a three-dimensional structure of a molecule. Structural changes in the molecule complex resulted in multiple characteristic scattering images over time. When a molecule is excited by a laser pulse, multiple vibrational quantum states are simultaneously excited. The superposition of several excited vibrational quantum states is called a wave packet. The researchers tracked the wave packet in three-dimensional nuclear coordinates and found that the first half round of chemical bonding was formed within 35 fs after photoexcitation. The second half of the reaction followed within 360 fs to complete the entire reaction dynamics.

They also accurately illustrated molecular vibration motions in both temporal- and spatial-wise. This is quite a remarkable feat considering that such an ultrafast speed and a minute length of motion are quite challenging conditions for acquiring precise experimental data.

In this study, the KAIST-IBS research team improved upon their 2015 study published by Nature. In the previous study in 2015, the speed of the x-ray camera (time resolution) was limited to 500 fs, and the molecular structure had already changed to be linear with two chemical bonds within 500 fs. In this study, the progress of the bond formation and bent-to-linear structural transformation could be observed in real time, thanks to the improvement time resolution down to 100 fs. Thereby, the asynchronous bond formation mechanism in which two chemical bonds are formed in 35 fs and 360 fs, respectively, and the bent-to-linear transformation completed in 335 fs were visualized. In short, in addition to observing the beginning and end of chemical reactions, they reported every moment of the intermediate, ongoing rearrangement of nuclear configurations with dramatically improved experimental and analytical methods.

They will push this method of 'real-time tracking of atomic positions in a molecule and molecular vibration using femtosecond x-ray scattering' to reveal the mechanisms of organic and inorganic catalytic reactions and reactions involving proteins in the human body. "By directly tracking the molecular vibrations and real-time positions of all atoms in a molecule in the middle of reaction, we will be able to uncover mechanisms of various unknown organic and inorganic catalytic reactions and biochemical reactions," notes Dr. Jong Goo Kim, the lead author of the study.

Publications:

Kim, J. G., et al. (2020) ‘Mapping the emergence of molecular vibrations mediating bond formation’. Nature. Volume 582. Page 520-524. Available online at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2417-3

Profile: Hyotcherl Ihee, Ph.D.

Professor

hyotcherl.ihee@kaist.ac.kr

http://time.kaist.ac.kr/

Ihee Laboratory

Department of Chemistry

KAIST

https://www.kaist.ac.kr

Daejeon 34141, Korea

(END)

2020.06.24 View 21306

Every Moment of Ultrafast Chemical Bonding Now Captured on Film

- The emerging moment of bond formation, two separate bonding steps, and subsequent vibrational motions were visualized. -

< Emergence of molecular vibrations and the evolution to covalent bonds observed in the research. Video Credit: KEK IMSS >

A team of South Korean researchers led by Professor Hyotcherl Ihee from the Department of Chemistry at KAIST reported the direct observation of the birthing moment of chemical bonds by tracking real-time atomic positions in the molecule. Professor Ihee, who also serves as Associate Director of the Center for Nanomaterials and Chemical Reactions at the Institute for Basic Science (IBS), conducted this study in collaboration with scientists at the Institute of Materials Structure Science of High Energy Accelerator Research Organization (KEK IMSS, Japan), RIKEN (Japan), and Pohang Accelerator Laboratory (PAL, South Korea). This work was published in Nature on June 24.

Targeted cancer drugs work by striking a tight bond between cancer cell and specific molecular targets that are involved in the growth and spread of cancer. Detailed images of such chemical bonding sites or pathways can provide key information necessary for maximizing the efficacy of oncogene treatments. However, atomic movements in a molecule have never been captured in the middle of the action, not even for an extremely simple molecule such as a triatomic molecule, made of only three atoms.

Professor Ihee's group and their international collaborators finally succeeded in capturing the ongoing reaction process of the chemical bond formation in the gold trimer. "The femtosecond-resolution images revealed that such molecular events took place in two separate stages, not simultaneously as previously assumed," says Professor Ihee, the corresponding author of the study. "The atoms in the gold trimer complex atoms remain in motion even after the chemical bonding is complete. The distance between the atoms increased and decreased periodically, exhibiting the molecular vibration. These visualized molecular vibrations allowed us to name the characteristic motion of each observed vibrational mode." adds Professor Ihee.

Atoms move extremely fast at a scale of femtosecond (fs) ― quadrillionths (or millionths of a billionth) of a second. Its movement is minute in the level of angstrom equal to one ten-billionth of a meter. They are especially elusive during the transition state where reaction intermediates are transitioning from reactants to products in a flash. The KAIST-IBS research team made this experimentally challenging task possible by using femtosecond x-ray liquidography (solution scattering). This experimental technique combines laser photolysis and x-ray scattering techniques. When a laser pulse strikes the sample, X-rays scatter and initiate the chemical bond formation reaction in the gold trimer complex. Femtosecond x-ray pulses obtained from a special light source called an x-ray free-electron laser (XFEL) were used to interrogate the bond-forming process. The experiments were performed at two XFEL facilities (4th generation linear accelerator) that are PAL-XFEL in South Korea and SACLA in Japan, and this study was conducted in collaboration with researchers from KEK IMSS, PAL, RIKEN, and the Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute (JASRI).

Scattered waves from each atom interfere with each other and thus their x-ray scattering images are characterized by specific travel directions. The KAIST-IBS research team traced real-time positions of the three gold atoms over time by analyzing x-ray scattering images, which are determined by a three-dimensional structure of a molecule. Structural changes in the molecule complex resulted in multiple characteristic scattering images over time. When a molecule is excited by a laser pulse, multiple vibrational quantum states are simultaneously excited. The superposition of several excited vibrational quantum states is called a wave packet. The researchers tracked the wave packet in three-dimensional nuclear coordinates and found that the first half round of chemical bonding was formed within 35 fs after photoexcitation. The second half of the reaction followed within 360 fs to complete the entire reaction dynamics.

They also accurately illustrated molecular vibration motions in both temporal- and spatial-wise. This is quite a remarkable feat considering that such an ultrafast speed and a minute length of motion are quite challenging conditions for acquiring precise experimental data.

In this study, the KAIST-IBS research team improved upon their 2015 study published by Nature. In the previous study in 2015, the speed of the x-ray camera (time resolution) was limited to 500 fs, and the molecular structure had already changed to be linear with two chemical bonds within 500 fs. In this study, the progress of the bond formation and bent-to-linear structural transformation could be observed in real time, thanks to the improvement time resolution down to 100 fs. Thereby, the asynchronous bond formation mechanism in which two chemical bonds are formed in 35 fs and 360 fs, respectively, and the bent-to-linear transformation completed in 335 fs were visualized. In short, in addition to observing the beginning and end of chemical reactions, they reported every moment of the intermediate, ongoing rearrangement of nuclear configurations with dramatically improved experimental and analytical methods.

They will push this method of 'real-time tracking of atomic positions in a molecule and molecular vibration using femtosecond x-ray scattering' to reveal the mechanisms of organic and inorganic catalytic reactions and reactions involving proteins in the human body. "By directly tracking the molecular vibrations and real-time positions of all atoms in a molecule in the middle of reaction, we will be able to uncover mechanisms of various unknown organic and inorganic catalytic reactions and biochemical reactions," notes Dr. Jong Goo Kim, the lead author of the study.

Publications:

Kim, J. G., et al. (2020) ‘Mapping the emergence of molecular vibrations mediating bond formation’. Nature. Volume 582. Page 520-524. Available online at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2417-3

Profile: Hyotcherl Ihee, Ph.D.

Professor

hyotcherl.ihee@kaist.ac.kr

http://time.kaist.ac.kr/

Ihee Laboratory

Department of Chemistry

KAIST

https://www.kaist.ac.kr

Daejeon 34141, Korea

(END)

2020.06.24 View 21306 -

A Deep-Learned E-Skin Decodes Complex Human Motion

A deep-learning powered single-strained electronic skin sensor can capture human motion from a distance. The single strain sensor placed on the wrist decodes complex five-finger motions in real time with a virtual 3D hand that mirrors the original motions. The deep neural network boosted by rapid situation learning (RSL) ensures stable operation regardless of its position on the surface of the skin.

Conventional approaches require many sensor networks that cover the entire curvilinear surfaces of the target area. Unlike conventional wafer-based fabrication, this laser fabrication provides a new sensing paradigm for motion tracking.

The research team, led by Professor Sungho Jo from the School of Computing, collaborated with Professor Seunghwan Ko from Seoul National University to design this new measuring system that extracts signals corresponding to multiple finger motions by generating cracks in metal nanoparticle films using laser technology. The sensor patch was then attached to a user’s wrist to detect the movement of the fingers.

The concept of this research started from the idea that pinpointing a single area would be more efficient for identifying movements than affixing sensors to every joint and muscle. To make this targeting strategy work, it needs to accurately capture the signals from different areas at the point where they all converge, and then decoupling the information entangled in the converged signals. To maximize users’ usability and mobility, the research team used a single-channeled sensor to generate the signals corresponding to complex hand motions.

The rapid situation learning (RSL) system collects data from arbitrary parts on the wrist and automatically trains the model in a real-time demonstration with a virtual 3D hand that mirrors the original motions. To enhance the sensitivity of the sensor, researchers used laser-induced nanoscale cracking.

This sensory system can track the motion of the entire body with a small sensory network and facilitate the indirect remote measurement of human motions, which is applicable for wearable VR/AR systems.

The research team said they focused on two tasks while developing the sensor. First, they analyzed the sensor signal patterns into a latent space encapsulating temporal sensor behavior and then they mapped the latent vectors to finger motion metric spaces.

Professor Jo said, “Our system is expandable to other body parts. We already confirmed that the sensor is also capable of extracting gait motions from a pelvis. This technology is expected to provide a turning point in health-monitoring, motion tracking, and soft robotics.”

This study was featured in Nature Communications.

Publication:

Kim, K. K., et al. (2020) A deep-learned skin sensor decoding the epicentral human motions. Nature Communications. 11. 2149. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16040-y29

Link to download the full-text paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-020-16040-y.pdf

Profile: Professor Sungho Jo

shjo@kaist.ac.kr

http://nmail.kaist.ac.kr

Neuro-Machine Augmented Intelligence Lab

School of Computing

College of Engineering

KAIST

2020.06.10 View 14830

A Deep-Learned E-Skin Decodes Complex Human Motion

A deep-learning powered single-strained electronic skin sensor can capture human motion from a distance. The single strain sensor placed on the wrist decodes complex five-finger motions in real time with a virtual 3D hand that mirrors the original motions. The deep neural network boosted by rapid situation learning (RSL) ensures stable operation regardless of its position on the surface of the skin.

Conventional approaches require many sensor networks that cover the entire curvilinear surfaces of the target area. Unlike conventional wafer-based fabrication, this laser fabrication provides a new sensing paradigm for motion tracking.

The research team, led by Professor Sungho Jo from the School of Computing, collaborated with Professor Seunghwan Ko from Seoul National University to design this new measuring system that extracts signals corresponding to multiple finger motions by generating cracks in metal nanoparticle films using laser technology. The sensor patch was then attached to a user’s wrist to detect the movement of the fingers.

The concept of this research started from the idea that pinpointing a single area would be more efficient for identifying movements than affixing sensors to every joint and muscle. To make this targeting strategy work, it needs to accurately capture the signals from different areas at the point where they all converge, and then decoupling the information entangled in the converged signals. To maximize users’ usability and mobility, the research team used a single-channeled sensor to generate the signals corresponding to complex hand motions.

The rapid situation learning (RSL) system collects data from arbitrary parts on the wrist and automatically trains the model in a real-time demonstration with a virtual 3D hand that mirrors the original motions. To enhance the sensitivity of the sensor, researchers used laser-induced nanoscale cracking.

This sensory system can track the motion of the entire body with a small sensory network and facilitate the indirect remote measurement of human motions, which is applicable for wearable VR/AR systems.

The research team said they focused on two tasks while developing the sensor. First, they analyzed the sensor signal patterns into a latent space encapsulating temporal sensor behavior and then they mapped the latent vectors to finger motion metric spaces.

Professor Jo said, “Our system is expandable to other body parts. We already confirmed that the sensor is also capable of extracting gait motions from a pelvis. This technology is expected to provide a turning point in health-monitoring, motion tracking, and soft robotics.”

This study was featured in Nature Communications.

Publication:

Kim, K. K., et al. (2020) A deep-learned skin sensor decoding the epicentral human motions. Nature Communications. 11. 2149. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16040-y29

Link to download the full-text paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-020-16040-y.pdf

Profile: Professor Sungho Jo

shjo@kaist.ac.kr

http://nmail.kaist.ac.kr

Neuro-Machine Augmented Intelligence Lab

School of Computing

College of Engineering

KAIST

2020.06.10 View 14830 -

Researchers Present a Microbial Strain Capable of Massive Succinic Acid Production

A research team led by Distinguished Professor Sang Yup Lee reported the production of a microbial strain capable of the massive production of succinic acid with the highest production efficiency to date. This strategy of integrating systems metabolic engineering with enzyme engineering will be useful for the production of industrially competitive bio-based chemicals. Their strategy was described in Nature Communications on April 23.

The bio-based production of industrial chemicals from renewable non-food biomass has become increasingly important as a sustainable substitute for conventional petroleum-based production processes relying on fossil resources. Here, systems metabolic engineering, which is the key component for biorefinery technology, is utilized to effectively engineer the complex metabolic pathways of microorganisms to enable the efficient production of industrial chemicals.

Succinic acid, a four-carbon dicarboxylic acid, is one of the most promising platform chemicals serving as a precursor for industrially important chemicals. Among microorganisms producing succinic acid, Mannheimia succiniciproducens has been proven to be one of the best strains for succinic acid production.

The research team has developed a bio-based succinic acid production technology using the M. succiniciproducens strain isolated from the rumen of Korean cow for over 20 years and succeeded in developing a strain capable of producing succinic acid with the highest production efficiency.

They carried out systems metabolic engineering to optimize the succinic acid production pathway of the M. succiniciproducens strain by determining the crystal structure of key enzymes important for succinic acid production and performing protein engineering to develop enzymes with better catalytic performance.

As a result, 134 g per liter of succinic acid was produced from the fermentation of an engineered strain using glucose, glycerol, and carbon dioxide. They were able to achieve 21 g per liter per hour of succinic acid production, which is one of the key factors determining the economic feasibility of the overall production process. This is the world’s best succinic acid production efficiency reported to date. Previous production methods averaged 1~3 g per liter per hour.

Distinguished professor Sang Yup Lee explained that his team’s work will significantly contribute to transforming the current petrochemical-based industry into an eco-friendly bio-based one.

“Our research on the highly efficient bio-based production of succinic acid from renewable non-food resources and carbon dioxide has provided a basis for reducing our strong dependence on fossil resources, which is the main cause of the environmental crisis,” Professor Lee said.

This work was supported by the Technology Development Program to Solve Climate Changes via Systems Metabolic Engineering for Biorefineries and the C1 Gas Refinery Program from the Ministry of Science and ICT through the National Research Foundation of Korea.

2020.05.06 View 11711

Researchers Present a Microbial Strain Capable of Massive Succinic Acid Production

A research team led by Distinguished Professor Sang Yup Lee reported the production of a microbial strain capable of the massive production of succinic acid with the highest production efficiency to date. This strategy of integrating systems metabolic engineering with enzyme engineering will be useful for the production of industrially competitive bio-based chemicals. Their strategy was described in Nature Communications on April 23.

The bio-based production of industrial chemicals from renewable non-food biomass has become increasingly important as a sustainable substitute for conventional petroleum-based production processes relying on fossil resources. Here, systems metabolic engineering, which is the key component for biorefinery technology, is utilized to effectively engineer the complex metabolic pathways of microorganisms to enable the efficient production of industrial chemicals.

Succinic acid, a four-carbon dicarboxylic acid, is one of the most promising platform chemicals serving as a precursor for industrially important chemicals. Among microorganisms producing succinic acid, Mannheimia succiniciproducens has been proven to be one of the best strains for succinic acid production.

The research team has developed a bio-based succinic acid production technology using the M. succiniciproducens strain isolated from the rumen of Korean cow for over 20 years and succeeded in developing a strain capable of producing succinic acid with the highest production efficiency.

They carried out systems metabolic engineering to optimize the succinic acid production pathway of the M. succiniciproducens strain by determining the crystal structure of key enzymes important for succinic acid production and performing protein engineering to develop enzymes with better catalytic performance.

As a result, 134 g per liter of succinic acid was produced from the fermentation of an engineered strain using glucose, glycerol, and carbon dioxide. They were able to achieve 21 g per liter per hour of succinic acid production, which is one of the key factors determining the economic feasibility of the overall production process. This is the world’s best succinic acid production efficiency reported to date. Previous production methods averaged 1~3 g per liter per hour.

Distinguished professor Sang Yup Lee explained that his team’s work will significantly contribute to transforming the current petrochemical-based industry into an eco-friendly bio-based one.

“Our research on the highly efficient bio-based production of succinic acid from renewable non-food resources and carbon dioxide has provided a basis for reducing our strong dependence on fossil resources, which is the main cause of the environmental crisis,” Professor Lee said.

This work was supported by the Technology Development Program to Solve Climate Changes via Systems Metabolic Engineering for Biorefineries and the C1 Gas Refinery Program from the Ministry of Science and ICT through the National Research Foundation of Korea.

2020.05.06 View 11711 -

Scientists Observe the Elusive Kondo Screening Cloud

Scientists ended a 50-year quest by directly observing a quantum phenomenon

An international research group of Professor Heung-Sun Sim has ended a 50-year quest by directly observing a quantum phenomenon known as a Kondo screening cloud. This research, published in Nature on March 11, opens a novel way to engineer spin screening and entanglement. According to the research, the cloud can mediate interactions between distant spins confined in quantum dots, which is a necessary protocol for semiconductor spin-based quantum information processing. This spin-spin interaction mediated by the Kondo cloud is unique since both its strength and sign (two spins favor either parallel or anti-parallel configuration) are electrically tunable, while conventional schemes cannot reverse the sign.

This phenomenon, which is important for many physical phenomena such as dilute magnetic impurities and spin glasses, is essentially a cloud that masks magnetic impurities in a material. It was known to exist but its spatial extension had never been observed, creating controversy over whether such an extension actually existed.

Magnetism arises from a property of electrons known as spin, meaning that they have angular momentum aligned in one of either two directions, conventionally known as up and down. However, due to a phenomenon known as the Kondo effect, the spins of conduction electrons—the electrons that flow freely in a material—become entangled with a localized magnetic impurity, and effectively screen it. The strength of this spin coupling, calibrated as a temperature, is known as the Kondo temperature.

The size of the cloud is another important parameter for a material containing multiple magnetic impurities because the spins in the cloud couple with one another and mediate the coupling between magnetic impurities when the clouds overlap. This happens in various materials such as Kondo lattices, spin glasses, and high temperature superconductors.

Although the Kondo effect for a single magnetic impurity is now a text-book subject in many-body physics, detection of its key object, the Kondo cloud and its length, has remained elusive despite many attempts during the past five decades. Experiments using nuclear magnetic resonance or scanning tunneling microscopy, two common methods for understanding the structure of matter, have either shown no signature of the cloud, or demonstrated a signature only at a very short distance, less than 1 nanometer, so much shorter than the predicted cloud size, which was in the micron range.

In the present study, the authors observed a Kondo screening cloud formed by an impurity defined as a localized electron spin in a quantum dot—a type of “artificial atom”—coupled to quasi-one-dimensional conduction electrons, and then used an interferometer to measure changes in the Kondo temperature, allowing them to investigate the presence of a cloud at the interferometer end.

Essentially, they slightly perturbed the conduction electrons at a location away from the quantum dot using an electrostatic gate. The wave of conducting electrons scattered by this perturbation returned back to the quantum dot and interfered with itself. This is similar to how a wave on a water surface being scattered by a wall forms a stripe pattern. The Kondo cloud is a quantum mechanical object which acts to preserve the wave nature of electrons inside the cloud.